Lupine Publishers Journal of Surgery and Journal of Case Studies: Currently case studies drag the concentration of the investigators since each case present provides deep understanding in diagnosis and treatment methods. It is devoted to publishing case series and case reports. Articles must be genuine

Tuesday, December 17, 2019

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Utilitarian Value of Selected ...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Utilitarian Value of Selected ...: Lupine Publishers- Trends in Civil Engineering and its Architecture Abstract This method of Lightweight floor construc...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Climate Resilient Intervention...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Climate Resilient Intervention...: Abstract The Hindu Kush Himalaya (HKH) region has significant implications for the agro based economies of eight adjoining countrie...

Friday, December 13, 2019

Lupine Publishers |UK Gulf War Health Professional Veterans’ Perceptions of and Recommendations for Pre-Deployment Training: The Past Informing an Uncertain Future?

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Health Research and Reviews

For more Lupine Publishers Open

Access Journals Please visit our website:

http://lupinepublishers.us/

For more Research and Reviews on Healthcare articles Please Click Here:

https://lupinepublishers.com/research-and-reviews-journal/

To Know More About Open Access Publishers Please Click on Lupine Publishers

Follow on Linkedin : https://www.linkedin.com/company/lupinepublishers

Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/lupine_online

Background: The Gulf War is regarded as a unique war due to

its unconventional weaponry threat and the rare deployment

of a sizeable number of British non-regular troops. Using data collected

in 1991, 95 non-regular health professional veterans gave

perceptions of their pre-deployment military training and their related

recommendations.

Participants: The first cohort of participants was accessed

opportunistically and they invited a second cohort of veterans known

to them known to them and in similar military health professions.

Reservist participants (on the Reserve list) almost matched those

in the Voluntary Services (e.g. Territorial Army) in number.

Method: Qualitative and quantitative data were gathered at six months post War in the first of three six monthly postal

questionnaire surveys.

Results: Overall, most veterans found training adequate

or good but some one-third (particularly Reservists) found it poor or

bad in content and delivery. The minority recipients of stress

management training found it lacked personal relevance and attracted

trainers’ culture-related derision. Non-recipients believed that had it

been received it could have reduced pre-deployment stress.

Conclusion: Although many of the respondents’ recommendations have been met following the Gulf War, arguably fundamental

change to the military culture is of a slower pace.

Keywords: Gulf war; Reservists; Pre deployment Training; Stress management training

Abbreviations: TA: Territorial Army, CBW: Chemica Biological Warfare, SPSS: Statistical Package For The Social Sciences

The Context and Uniqueness of the Gulf War and its Relevance to the Present

The Gulf War (GW) 1991 is the only modern multi-national war

in which all participant United Kingdom (UK) troops were prepared

for chemical/ biological warfare (CBW). The Iraqi use of the

chemical agent chlorine in Iraq in 2007 [1] and later sarin in Syria

in August 2013, both against civilian populations, demonstrate that

where there is possession, this threat would seem to persist. In

November 1990, in response to the size of the Iraqi conventional and

unconventional weaponry threat, the potential for high casualties

and an acknowledgement by the UK Government of the insufficient

number of regular military medical personnel, part-time military

Voluntary Services (VS) health professionals (doctors, nurses,

and professions allied to medicine) were invited to volunteer [2].

Although some Territorial Army (TA) VS personnel responded

positively, the number was insufficient and consequentially those

on the ex-Regular Reserve List were called-up: an action not

undertaken since the Korean War (1950-53). Most of the called-up

and volunteer troops joined regular troops (deployed some months

earlier) in Saudi Arabia from December 1990 to early January 1991

[2]. In the UK, the importance of the impending War was hailed as a

new learning source for civilian nurses both from stand-by for war

casualties in UK hospitals and from active military service in Saudi

Arabia [3].

The Pre-Deployment Stressors

Several United States (US) authors [4,5] report that for US

Reservists, pre-deployment to the GW was an unusually short time

in which to make domestic preparations; wind-up civilian worklife,

mobilise into new military groups and receive training specific

to the requirements of deployment. Some US Reservists reported

dissatisfaction and distress, because they had not anticipated either

their call-up, or the stressful transition from civilian to soldier [5].

No published UK research could be found that mirrors the above

US findings but it is likely that some degree of similar disruptive

experience arose for UK Reservists as neither of these populations

lived or worked in military establishments. The Coalition’s military

personnel, drawn from 30 nations, also shared the anticipatory

stress associated with Iraq’s threatened use of CBW agents. In a

post war review article, it was suggested that this unconventional

threat produces intense fear in troops [6]. It is described as a

potent form of psychological warfare (whether it is real or not)

and one that does not discriminate between combatants and noncombatants

[7]. Several UK HPVs [8,9] have testified to the CBW

threat as their greatest source of fear. Furthermore, in a study of

UK troops during a real GW missile attack, O’Brien and Payne found

that despite training in the use of protective suits and medication,

troops’ acute anticipatory fear was triggered to the point of panic

rather than reduced [10]. Above all, Coalition troops entered this

war knowing that as Iraq had used CWB during the Iraq/ Iran War

of 1980-88 [11], history could repeat itself.

Pre-Deployment Training and the Military Culture

The ex-military writer McManners put forward the view that

UK military training facilitates the transition from civilian to soldier

with the fundamental aim of breaking down the entrant’s identity

and values by consent and replacing them with those that guide,

govern and sustain the military culture [12]. In the GW, re entry

to the military for some civilian nurses meant a radical change

from civilian nursing roles and responsibilities at a higher level

than they were hitherto accustomed. One British female Reservist

nurse described positively her ‘sound’ military training in the UK

before her deployment to a field hospital in Saudi Arabia [8]. She

learned medical skills for the treatment of casualties contaminated

CBW agents and underwent the British Army Trauma and Life

Support training programme. She recorded that as there were

only a few doctors in each field hospital in the GW, her role and

responsibilities were comparable to those of a junior doctor.

Before the GW, Brooking [13] wrote about the role of TA medical

and nursing units under contemporary war conditions She

suggests that those treating battle casualties, would become party

to war’s failure in terms of human vulnerability, rather than its

military and political success. Furthermore, the usual occupational

stressors found in civilian medical and nursing settings become

heightened with the additional stressors that affect all personnel

in war-service. Being in a military health professional role does not

exempt the person from fulfilling that of the soldier. This requires

discipline, obedience, conformity and a strong sense of duty:

qualities developed from early training [12]. At the time of the GW,

McManners [12] questioned the appropriateness of the UK Army’s

culture of keeping ‘a stiff upper lip’ thereby perpetuating the macho

‘ancient warrior type’, given the deployment of some 1000 British

female troops, some in frontline roles [13,14]. This cultural myth is

believed to help individuals during adversity overcome being seen

as weak and stigmatised as such by peers and those of higher rank

[15]. Despite efforts by the military to counter stigma, this cultural

element reportedly continues in the UK military to the present day

[16].

Design and Method

Using a longitudinal design comprising three postal questionnaire

surveys, each six months apart, this article’s data were collected

in the first survey conducted some six months after the Gulf

War’s end in 1991. Following a pilot study that refined the questionnaire’s

content and format with 5 HPVs, the questionnaire comprised

closed questions with opportunity for free text justification

following each response. This mixed methods approach (qualitative

and quantitative) maximised the potential for a greater depth of

understanding of the HPVs’ experiences than either method when

employed alone [17].

Sample Size and Selection

A total of 131 letters of invitation to participate in the study

were distribute via an intermediary HPV nurse already known to the

author. The first 57 HPVs responded positively and through them a

further 38 militarily and professionally similar participants were

contacted as a snowball technique. The final sample comprised: 47

Reservists (26 called up and 21 volunteers) and 48 VS volunteers

(43 TA personnel and 5 Welfare Officers). Following a further round

of study information-giving and consent-seeking, the estimated

return-rate was high (71%), which suggests that the HPVs were

keen to tell their story.

Ethical Considerations

The general principles of doing no harm; informed consent; the

acceptance of autonomy over of compliance, and respect for rights

to privacy, anonymity and confidentiality were upheld throughout

the research [18]. Authoritative military and academic advice was

taken throughout the study to avoid potentially sensitive issues.

All information forwarded to the HPVs cautioned them against

breaching the Official Secrets Act. The data were held securely and

in accordance with the Data Protection Act, 1987 and its update in

1998.

Mode of Analysis

Quantitative dichotomous data were analysed using Statistical

Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 22 and used logistic

regression with a forward stepwise Wald as the main predictive test.

Qualitative data in the form of the HPVs’ comments were examined

first by two researchers independently identifying key words or

phrases then categorised as key word or phrase labels. The latter

were formulated to capture as closely as possible the meaning of the

HPVs’ original words or phrases, as recommended by Krippendorff

[19]. The two researchers then made cross comparisons to reach

consensus as to themes and sub themes.

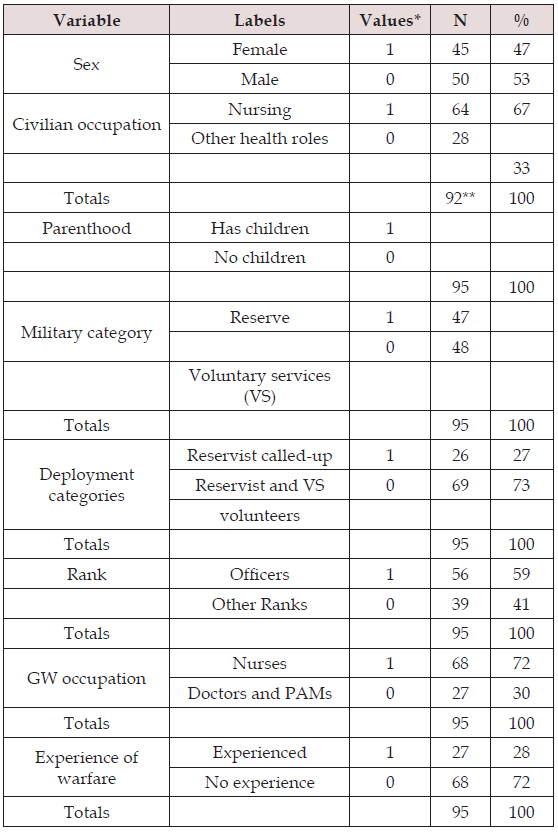

Characteristics of the Participant Sample

Personal, professional and military characteristic data were

formatted mainly as dichotomous variables to facilitate the use

of Logistic Regression, as shown in Table 1. The mean age of

participants was 37. When the figures for the civilian occupations

of the 95 HPVs were cross tabulated with the HPVs’ qualifications,

67 held nursing qualifications and of these, 49 (73%) worked as

Registered General Nurses; 4 (6%) as Registered Mental Nurses,

and the remaining 14 (21%) were State Enrolled Nurses. All other

health professionals other than combat technicians worked in

the same civilian professional roles as in the GW. Combat medical

technicians (similar to civilian ambulance paramedics) worked in

non-health civilian roles prior to the GW. Of the 95 HPVs, 27 (28%)

had previous warfare experience, of whom, 17 (17%) were in the

Reserve, 10 (11%) were in the TA VS and the remaining 68 (72%)

had no experience. The average length of time spent in the Gulf was

2.7 months. When the HPVs’ data for ‘length of time in the Gulf’

were compared with their deployment military categories using a

Mann-Whitney U test, Reservists were found to have spent less time

in deployment (mean rank=37.16) than those in the VS who spent

longer (mean rank = 58.61) and this difference was significant

(U=618.500, Z= -2.414, p<0.01). This suggests that Reservists were

deployed later to the Gulf than those in the TA VS.

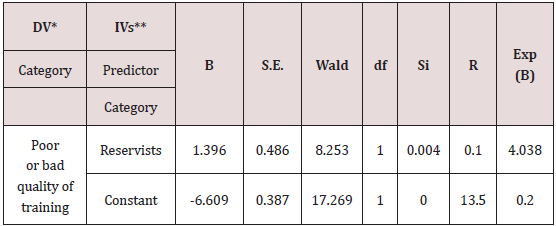

The HPVs’ Receipt of Training and Perceptions of its Quality

During the pre-deployment phase, most of the 95 HPVs received

training at home-based military establishments, although some

training occurred in the Gulf. When asked to give their opinion of

‘the quality of training’ using a four-point value scale, 21 (22%)

HPVs indicated that it was ‘excellent’, 45 (47%) said that it was

‘adequate’; 23 (24%) found it to be ‘poor’, and 6 (6%) said that it

was ‘bad’. When the 95 HPVs’ data for ‘time spent in deployment’

(in weeks) were compared with those for ‘the quality of training’

(reduced to a binary format using an independent t test), the 66

HPVs with ‘adequate/ good training’ spent longer in deployment

(mean = 2.76, standard deviation = 0.498) than the 29 with

‘poor/ bad training’ (mean = 2.41, standard deviation 0.628). This

difference was significant (f=6.33, t=2.86, df=93, p<0.05). Using the

data for opinion of the quality of training as the dependent variable

(DV) for logistic regression, the original four values were reduced

to ‘excellent/adequate training = 0’ and ‘poor/bad training’ = 1’ and

this was entered with sample characteristics as the independent

variables (IVs). As shown in (Table 2), military category was found

to be the best predictor of the HPVs’ quality of pre-deployment

training, with Reservists (value = 1) having a significantly increased

likelihood of perceiving training as ‘poor or bad’ (value = 1).

Table 2: Logistic regression between the HPVs’ perceived quality

of training with sample characteristics (n=95).

Perceived Quality of Training with Sample Characteristics (N=95)

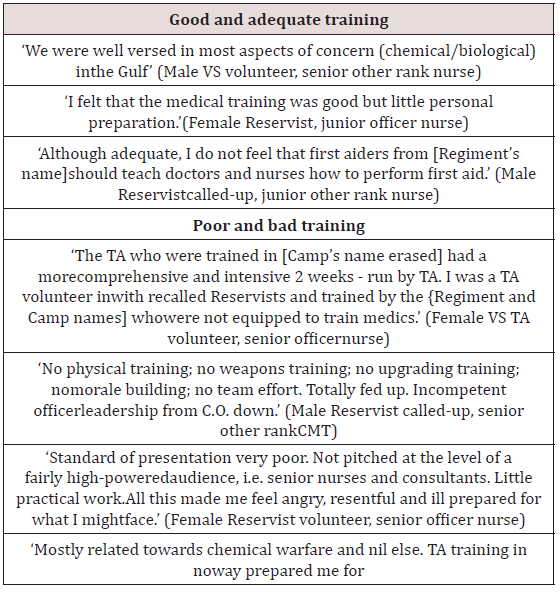

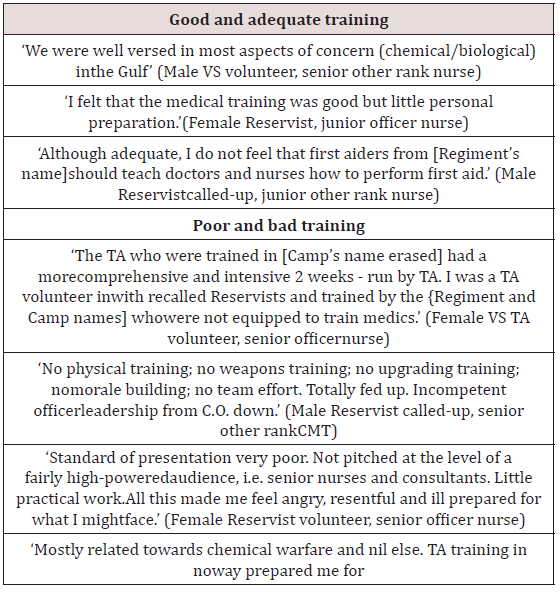

The HPVs justified their responses to the quality of training

question. Content analysis of their comments revealed some

explanations for the difference in perceptions between Reservists

with those in the TA as shown in (Table 3). The TA HPVs who

attended training given by TA trainers were the most positive

but when recording training as ‘adequate’ there were complaints.

Some HPVs wanted more training related to CBW unconventional

weaponry, whereas others (with hindsight) portrayed that this was

over-emphasised at the expense of the more common injuries from

conventional weaponry that they had treated. The presentation of

first aid was singled out as being too basic in comparison with the

level of knowledge of the recipient audience. For some Reservists

called-up as the latecomers to pre-deployment, UK-based training

seemed to have run out of time and organisation by the end of

1990, thus they received some training after arrival in the Gulf. The

following Reservist comment describes a somewhat chaotic scene

at his UK-based training centre: Total lack of co-ordination and

shortage of staff - 60% of the time spent in queues.’ (Male Reservist

volunteer, senior other rank CMT)

Table 3: Logistic regression between the HPVs’ perceived quality

of training with sample characteristics (n=95).

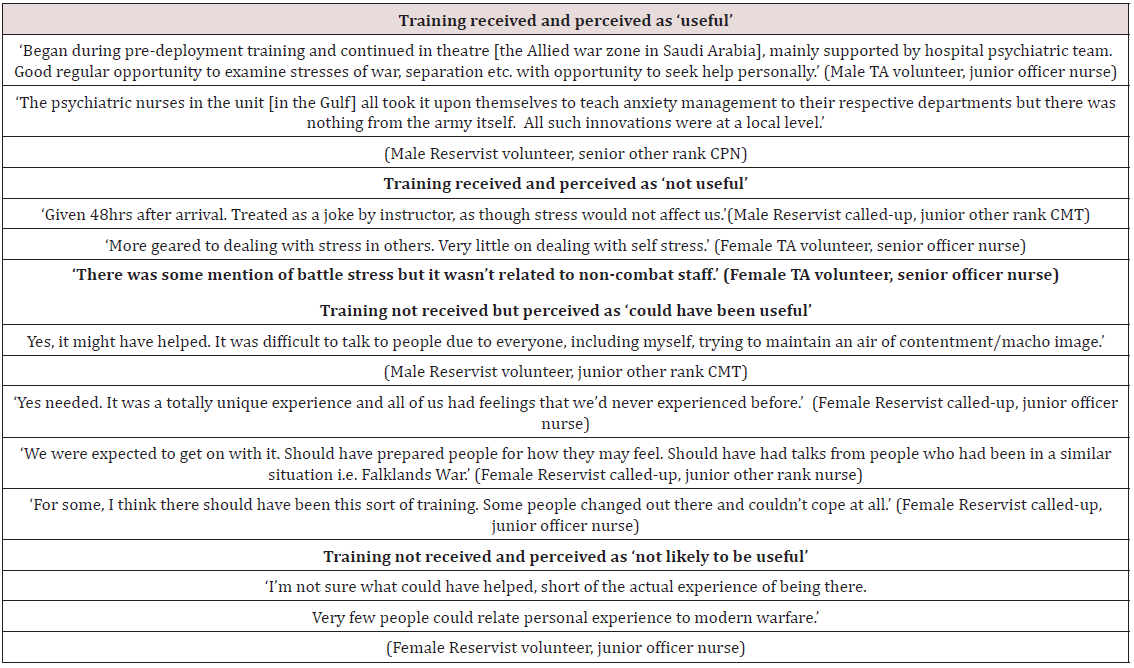

The HPVs’ Perceptions of Stress Management Training

Twenty-seven (28%) of the 95 HPVs recorded that they had

received stress management training as a part of their overall

training but of these, only nine described it as ‘helpful’. As no

significant predicator was identified (p>0.05) from logistic

regression, its receipt or not was not associated with the HPVs

personal or military characteristics. This is perhaps because this

form of training did not appear to have a consensus as to its place

within training or what its content should be. As shown in (Table 4),

of the recipients who found this training ‘helpful’, their comments

suggest that they received it at different locations and times

during pre-deployment and deployment in the Gulf. This diversity

is illustrated first by the recipients of this training in the Gulf

reporting positively on spontaneous out-reach stress management

training sessions provided by nurses from a UK psychiatric team.

Their positive comments indicate that not only was it informative

in covering the main stressors and stresses, but sessions were

backed up with practical support for the individual. In contrast,

of the HPVs in receipt of stress management training within their

main UK-based pre-deployment training, negativity was reported

either concerning the derisive attitudes of the trainers in their

delivery of psychological content, or because it was not directed

sufficiently towards the HPVs’ perceived needs as individuals and

as non-combatants. Non-recipients frequently commented that

had this training been received, it could have been a useful coping

mechanism for those affected by stress during pre-deployment.

However, some HPVs believed that as the GW was unique, this

precluded second-guessing either the stressors to be encountered

or their reactions to them. As one HPV said: ‘No-one could foresee

how we would feel, we were just expected to get on with the job.’

Finally, a few non-recipients suggested that this form of training

was not of importance. Of these, one male Reservist medical officer

appears to unwittingly accept the military cultural avoidance of

stress effects by making light of such training : ‘It would not have

been taken seriously. It probably would have been inappropriate.’

The HPVs’ Recommendations to Improve Training

The HPVs provided 97 recommendations to improve predeployment.

Of these 21 (22%) were related to training. The first

theme called for greater realism about the political context and

nature of modern of warfare from those with first-hand experience.

‘A talk/discussion from someone who in a down to earth way could

talk about their experience of modern warfare’. (Female Reservist

volunteer, junior officer nurse) The second theme requested that

training should be relevant to the circumstances of the war; their

roles and skills within it, and acknowledge the differences between

civilian with military practices. ‘The difference between service/

civilian medical practices must be emphasised. Field conditions

should be practised.’ (Male TA volunteer, junior officer nurse)

‘Weapons training. More time for extended role training before

departure.’ (Female TA volunteer, junior officer nurse) ‘If this

questionnaire is to be of use, it must emphasise the extreme lack

of training/equipment at our disposal during the Gulf War that

needs to be addressed.’ (Male Reservist called-up, senior other rank

CMT). More emphasis upon psychological support to cope with

the threats to person and also the stress of entry to new military

groups was suggested in the third theme. ‘More emphasis upon the

psychological changes that may effect people.’ (Female TA volunteer,

senior officer nurse) ‘Briefings and lectures on living and working

in confined areas and codes of behaviour between groups’ (Female

TA volunteer, senior officer nurse). Finally, in the last theme, both

Reservists and TA participants suggested increasing the annual

military training for Reservists. ‘As a Reservist, we should have

training sessions every year. …you simply have to turn up x 1 per

year, watch a film, collect £75 and go home.’ (Female Reservist

called-up, junior officer nurse)

Research concerned with UK GW pre-deployment training for

Reservists and VS TA personnel (or for any war preceding or after

it) appears to be sparse, despite the general recognition that it sets

the psychological tone for deployment with those the least trained

liable to experience the greatest fear [12].

The HPVs first theme called for greater realism during training

from those who have experienced war first-hand. This could

suggest that with hindsight, the HPVs recognised that realism could

have increased their sense of internal control and by association,

their resilience to stress [20]. US research related to the later Iraq

War and Afghanistan War claims that little has changed to diminish

the pre-deployment stressors evident in and since the GW [21].

However, over the years since the GW, the UK Government has

increasingly shown commitment to greater openness, support for

and recognition of value of Reserve forces, as reflected in the Armed

Forces Covenant published in 2011[22] and in the presentation

of policy in 2013 (both by the UK Ministry of Defence) for the

restructuring of the Armed Forces [23]. In this research, a sizeable

number of GW Reservist veterans perceived their pre-deployment

training as an inadequate preparation for the GW. As ex Regulars

with greater experience of warfare but little on-going training

since leaving the military, their lack of continuity could have made

them feel less prepared than those in the TA VS with their regular

peacetime training and possibly greater collective camaraderie. De

la Billiere acknowledges the pressure upon Reservists in having

to learn quickly following arrival in the Gulf due to their shortfall

in their UK-based pre-deployment training [2]. Deficits in first

aid training raised by some HPVs had already been reported in

a negative appraisal of the British Army’s provision of first aid

published around the time of the GW [24]. Shephard [25] suggests

that the high prevalence of post-war mental health problems in

veterans of the Falklands War, also reported by several other authors

[26,27] increased psychiatric services for UK troops in the GW war

zone. However, despite new services, stress management training

did not seem to have filtered down into pre-deployment training

with any consistency. Instead it was described as piecemeal, open

to derision, focussed mainly on combat casualty care, and delivered

in the Gulf too late after distressing events (such as SCUD missile

attacks). In contrast, what the HPVs clearly wanted was pro-active

training in self-management techniques to bolster their coping

mechanisms against the pre-deployment occupational and intermilitary

group stressors encountered but not foreseen.

Across time, several authors have reported upon improved

methods of stress management for non-combatants and

combatants. These include psychiatric team outreach interventions

[28,29] and the British Royal Marines’ peer-delivered trauma risk

management (TRIM) programme, designed to be pro-active in

overcoming the stigma arising from battle stress [30]. However,

these initiatives accentuate an ongoing military cultural dilemma.

Nash (2007) [31] contends that the military purpose in war has

no parallel in normal civilian life (and by inference neither has its

culture). He refutes the usefulness of overt psychological training

on the basis that leadership, training, and unit cohesion are

adequate to support troops with stress reactions. In contrast, other

authors acknowledge that the perceived stigmatising attitudes

within the military culture can inhibit UK [17] and US troops [32]

from accessing psychiatric help. Some authors argue that the way

a military person sees him/herself is the strongest form of stigma,

hence they recommend that for culture to change, effort needs to

focus upon improving the locus of control of the individual [16].

Osorio et al. [33] report that between 2008-2011, the military

has made considerable efforts to reduce stigma and of these, predeployment

briefings may have been beneficial but in general little

has been subjected to research evaluation.

It is over a quarter of a century since the end of the Gulf War.

The HPVs recommendation for more relevant training is largely

being met for the TA VS by the current restructuring of the

military’s manpower that will be on going until 2020 [34]. Major

changes to training and other conditions for the newly named Army

Reserve Forces (previously the TA) are reported on many online

Government and military sites. Amongst these, aligning Reservists

more closely with regular troops through shared training and

unit ‘pairing’ is recommended. In the case of military medical

services, the Reservists’ training will be linked more closely to the

competencies of the National Health Service. Training for the new

Reserve can be as little as 19 days per annum for specialist units or

one evening a week, several weekends and a 15 day training course

per annum for others. However, recruitment has been slow and has

not as yet reached the target of 30,000 new Reserve recruits by

2018-2019 [34]. Among the explanations for this shortfall, several

authors suggest that Reservists consider and experience different

challenges in their military service when compared to the Regular

Forces. These are related to the role of the military in society and

including challenges in the welfare of families, overcoming difficult

employers; and an observed higher level of post deployment mental

illness in Reservists than in Regulars [32,34]. It is of note that little

reference to those on the Reserve List could be found beyond the

hope that they would become recruits to the new Reserve Army

[35].

Although considerable effort was made to recruit a sample

of health professionals to represent those needed in the Gulf war

zone, the participants may not form a representative sample of

all health professionals sent to the Gulf: a population of unknown

number at that time. Furthermore, access to a suitable military

control population in the UK was also not made possible. For

these reasons, generalisation is limited. The findings from closed

questions with qualitative justifications are believed however to

provide a trustworthy representation of the perceptions of these

particular GW HPVs.

The HPVs’ recommendations to improve training largely seem

to have been addressed in current reforms to the military in the UK.

In the case of stress management, although it may be unrealistic

to foresee the eradication of war-related stress, ways of lessening

its impact without weakening resilience has become a healthy

aim. However, it seems that the military culture is slow to change.

Perhaps this will be spurred by new larger Reserve force which

could find the ‘ancient warrior-type’ less appealing. For, separating

the soldier from the civilian through training inevitably will become

more difficult in a future where the Reservist is likely be much more

openly mindful of family and civilian occupation than that of going

to war.

http://lupinepublishers.us/

For more Research and Reviews on Healthcare articles Please Click Here:

https://lupinepublishers.com/research-and-reviews-journal/

To Know More About Open Access Publishers Please Click on Lupine Publishers

Follow on Linkedin : https://www.linkedin.com/company/lupinepublishers

Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/lupine_online

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Medical Procedure Guide

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Medical Procedure Guide: Lupine Publishers | Open access Journal of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Opinion This book provides a comprehensive gui...

Wednesday, December 11, 2019

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Caries Survey in 3-5 Year Old ...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Caries Survey in 3-5 Year Old ...: Lupine Publishers | Journal of Pediatric Dentistry Impact Factor Abstract Introduction: Dental caries is considered the mo...

Tuesday, December 10, 2019

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers-Msct In Diagnosis of Congenital ...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers-Msct In Diagnosis of Congenital ...: Lupine Publishers | Advancements in Cardiovascular Research Abstract Background: Congenital heart diseases associated with m...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Congenital Craniofacial and Ce...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Congenital Craniofacial and Ce...: Lupine Publishers | Journal of Otolaryngology Research Impact Factor Abstract Congenital cysts, sinuses and fistulas of the...

Friday, December 6, 2019

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers-The Left Common Carotid Artery R...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers-The Left Common Carotid Artery R...: Lupine Publishers | Advancements in Cardiovascular Research Abstract A young female patient of 15y.o presented at my hospital...

Lupine Publishers |Early Decompressive Craniectomy for Post- Thrombolysis Symptomatic Intracranial Haemorrhage

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Health Research and Reviews

Key Message

Keywords: Decompressive craniectomy; Intravenous thrombolysis; Symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage; Thromboelastography

Introduction

Case report

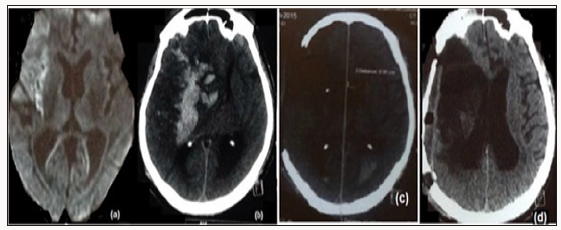

Figure 1: (a) Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (diffusion weighted image) done at presentation shows acute infarction

of the right superior middle cerebral artery. (b) Non contrast CT of the brain done 8 hours after thrombolysis showed

haemorrhage in the infarct resulting in mid line shift and mass effect. (c) Non Contrast CT of the brain done on the next

day after decompressive craniectomy and hematoma evacuation revealed no new bleed and resolving mass effect.(d) Non

Contrast CT of the brain following cranioplasty.

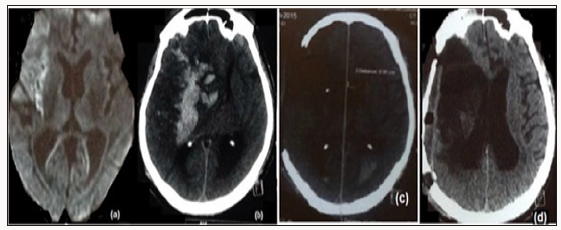

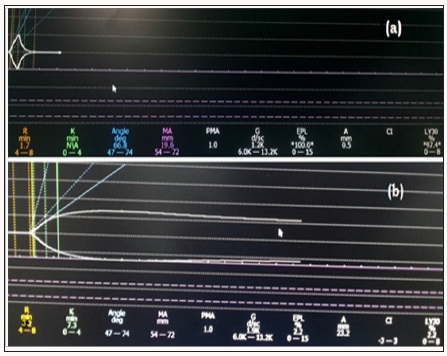

Figure 2: (a) Thromboelastograph trace obtained after 8hr of thrombolysis with R-1.7min, α-66.80, MA-19.6mm, LY30-97.4%,

EPL%-100%. These features are characteristic features of fibrinolysis with normal R time, decreased maximum amplitude

(MA), raised LY30 (percentage decrease in maximum amplitude or lysis after 30 minutes) and raised EPL. EPL represents the

computer prediction of 30mins clot lysis based on interrogation of actual rate of diminution of the trace commencing 30sec

post MA with a normal value of <15%. It is the earliest indicator of abnormal lysis. (b) Thromboelastographic trace obtained

after infusion of cryoprecipitate and fresh frozen plasma with R-6min, K-1.5min, α-67.50, MA-49.6mm, LY30-0%, EPL%-0%.

Discussion

Recombinant t-PA is an exogenous stimulator of the fibrinolytic system that enhances local fibrinolysis by converting plasminogen to plasmin. Our concern was the increased risk of peri operative haemorrhage associated with high mortality due to the persistent effect of TPA. With regard to the pharmacokinetics, half-life of rt- PA is <5 min, with clearance rate of 380-570mL/min [7]. Hence, 80% of rt-PA is cleared from the plasma within 10 minutes of administration. Despite short half-life of rt-PA fibrinolytic effects peak at 4hours and can persist up to 24-48hours [7]. The clinical dilemma in such a scenario was to wait for the disappearance of the fibrinolytic effects to avoid peri operative bleeding at the cost of outweighing the benefits of early DC in reducing the raised ICP. The other option was to efficiently detect and correct the coagulation abnormality by transfusing specific blood products to minimize the risk of bleeding. We had the benefit of thromboelastography at our institute to guide.com with the correction of the deranged coagulation profile before proceeding for DC. S Takeuchi et al. retrospectively reviewed 20 patients who underwent DC for malignant hemispheric infarction after IV TPA administration, with another 20 patients undergoing DC without prior IV TPA administration [8]. They observed intracranial bleeding or worsening of pre existing ICH in two patients (10%) in each group, but tPA was not thought to be contributory to the hemorrhagic events because of the long intervals between the IV tPA and DC(185 and 136h, respectively). However, fibrinolytic markers, such as fibrinogen or fibrin degradation products were unfortunately not measured in the above series.

Thrombelastography or TEG measures the physical properties of the clot via a pin suspended in a cup from a torsion wire connected with a mechanical-electrical transducer. TEG is different from other coagulation tests as it provides global information on the dynamics of clot development, stabilization and dissolution [9]. It assesses both thrombosis and fibrinolysis. Its role is established in cardiac and liver transplant surgery and is being increasingly explored to study role of fibrinolysis in early trauma coagulopathy [10]. Although routinely tested coagulation parameters (BT, CT, PTI, and APTT) were also normal in our case but TEG was characteristic of enhanced fibrinolysis. Hence, we transfused cryoprecipitate and fresh frozen plasma after which the TEG was normal, and we could proceed with surgery.

Conclusion

For more Lupine Publishers Open Access Journals Please visit our website:

http://lupinepublishers.us/

For more Research and Reviews on Healthcare articles Please Click Here:

https://lupinepublishers.com/research-and-reviews-journal/

To Know More About Open Access Publishers Please Click on Lupine Publishers

Follow on Linkedin : https://www.linkedin.com/company/lupinepublishers

Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/lupine_online

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Risk Stratification at Patient...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Risk Stratification at Patient...: Lupine Publishers | Open access Journal of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Short Communication It is noted, that today th...

Thursday, December 5, 2019

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | The Tall Poppy Syndrome in Ort...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | The Tall Poppy Syndrome in Ort...: Lupine Publishers | Journal of Orthopaedics Opinion The Tall Poppy Syndrome (TPS) is a metaphor which symbolizes viewing ...

Wednesday, December 4, 2019

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Focusing on Food Security or T...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Focusing on Food Security or T...: Abstract Maize and cotton are two crops that are highly produced in North Benin. Their production has advantages as well as constr...

Tuesday, December 3, 2019

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Spatial Analysis of Data on th...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Spatial Analysis of Data on th...: Abstract The article examines the issues of studying the degree of susceptibility of sloping lands in Azerbaijan in the example of...

Monday, December 2, 2019

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Excellent Crystal Coloration a...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Excellent Crystal Coloration a...: Lupine Publishers- Organic and inorganic chemical sciences The analysis of the impurity content crystals grown in sodium carbonate ...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Fibonacci Circle in Fashion De...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Fibonacci Circle in Fashion De...: Lupine Publishers | Journal of Textile and Fashion Designing Editorial Fibonacci circle is a pattern which is created on the...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| A Standard Pediatric Dental Clinic

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| A Standard Pediatric Dental Clinic : Lupine Publishers| Journal of Dentistry and Oral Health Care Aft...

-

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| A Standard Pediatric Dental Clinic : Lupine Publishers| Journal of Dentistry and Oral Health Care Aft...

-

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Health Research and Reviews Abstract Metabolism is the process your body uses to make energy f...

-

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Health Research and Reviews bstract Purity of the person is guarantee of his health. Spiritual and...