Lupine Publishers Journal of Surgery and Journal of Case Studies: Currently case studies drag the concentration of the investigators since each case present provides deep understanding in diagnosis and treatment methods. It is devoted to publishing case series and case reports. Articles must be genuine

Tuesday, June 29, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| Synthesis and Anxiolytic Activi...

Monday, June 28, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Prevalence of Postpartum Depre...

Lupine Publishers| Association of Blood Group with Tea Likeliness

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Health Research and Reviews

Abstract

Keywords:Tea likeliness; Blood grouping system; Tea lovers

Introduction

ABO blood group system is one of the most common Blood group systems of human beings which are categorized according to the inherited elements of Erythrocytes. It is determined by the presence of Antigens A and B which are present on the surface of red blood cells. Antigens (Red blood cells) and Antibodies (Serum) are produced opposite to each other in ABO blood group system according to which Blood transfusion occurs from person to person. ABO Antibodies in the serum are formed naturally. ABO antigens produced before birth and remain throughout life. ABO blood group system was first introduced by Austrian Immunologist KARL LANDSTEINER in 1901. There are four major types of ABO blood group system: Blood group A, Blood group B, Blood group AB, Blood group O. Blood group A contains Antigen A and the Antibodies produced will be Anti-B and its genotype will be AA or AO. Persons having Blood group A can donate blood to the persons having Blood group A or AB. Blood group A is the most common in AUSTRALIA. Blood group B contains Antigen B and the Antibodies produced will be Anti-A and its genotype will be BB or BO. Persons having Blood group B can donate blood to the persons having Blood group B or AB. Blood group B is the most common in ASIA. Blood group AB contains Antigen A and Antigen B and no Antibodies will be produced and its genotype will be AB. Persons with Blood group AB can donate blood to the persons having Blood group AB. Blood group AB is the universal recipient. Blood group O contains no Antigens but Antibodies produced will be Anti-A and Anti-B and its genotype will be OO. Persons having Blood group O can donate blood to the persons having Blood group O, A, B or AB. Blood group O is the Universal donor. Blood group O is the most common Blood type throughout the World [1]. The Rh Blood group is one of the complex blood groups in humans and it has become the second most important Blood group system after ABO system. It was first discovered in Rhesus monkey. The term Rh factor consists of Rh positive and Rh negative refer to the Rh (D) antigen. After testing the ABO Blood group in human beings, it is very important to check Rh status.

Hence, Blood groups can be A+, A-, B+, B-, AB+, AB-, O+ or O-. Rhesus positive consists of a protein (D antigen) which is found on the surface of our red blood cells. Rh positive blood type is present in almost 85% of the population. Persons with Rh+ blood can receive blood from persons with Rh- blood without any problem. Rhesus negative does not consist of a protein (D antigen. Rh negative is rare in the population. Persons with Rh- blood does not have Rh Antibodies naturally in the Blood plasma. Persons with Rh- blood cannot receive blood from persons having Rh+. Rh incompatibility can cause a serious disease like Erythroblastosis fetalis. It is an hemolytic disease in the new born child in which an Rh-/ type O mother carrying an Rh+/ type A, B, or AB foetus causes resistant to the Rh+ factor and start producing antibodies against the foetus blood group which leads to anemia in the child [2]. Tea is an aromatic beverage which is prepared by gushing hot or boiling water from the young leaves of Camellia Sinensis (Tea plant), found in Asia and it is the most widely consumed drink in the World after water. The story of tea began in china in 2737 BC and then, this beverage spreaded in the whole World like fire. Tea contains L-theanine, theophylline, caffeine and some amount of nicotine due to which man becomes its addictive and it regulates our Blood. More than four cups of tea per day are not good for our health. There are four basic types of Tea: White tea, Green tea, Oolong tea and Black tea. The benefits of taking tea include alerting our brain for some time and reducing heart attack. Tea also helps in reducing body weight and protecting our bones. Its side effects include headache, sleeping problems, diarrhea, kidney problems and convulsions. Besides its side effects, there are many Tea lovers i.e. 9 out of 10 persons like tea very much. Tea is like a passion for tea lovers or it is a hope for them to spend their hectic day along with tea because it is a symbol of relaxation for them. Besides this, Tea time is a family time in which everybody enjoys a lot. Some tea lovers don’t care about their health and take tea many times a day which can be dangerous for them. The objective of the present study was to interlink Blood Grouping with Tea likeliness.

Materials and Method

Blood Grouping

First of all, we laid out all the components of the kit in front of you which consisted of Antiserum A, Antiserum B, Antiserum D, Glass slides and Prickers (Needles). Secondly, took a pricker (needle) and pricked the upper portion of a finger for taking some drops of blood of a subject. Then, we made three spots of blood of considerable amount on a slide and added a small drop of Antisera A, Antisera B and Antisera D. After adding this, we mixed up little with the needle and after few seconds, noted the Agglutination in Blood drops. The Agglutination by the Antisera A and Antisera B in the drops of blood decided the blood group of that subject while Antisera D showed the positivity and negativity of the Blood. We Checked the Blood group of some subjects and the subjects whose blood drops containing Antisera B and Antisera D agglutinated, it meant subjects had Blood group B positive. The subjects whose Blood drops containing Antisera A and Antisera D agglutinated, it meant subjects had Blood group A positive. The subjects whose Blood drops containing Antisera A, Antisera B and Antisera D agglutinated, it meant subjects had AB positive Blood group. The subjects whose Blood drops containing Antisera A and Antisera B did not agglutinate while Blood drop containing Antisera D agglutinated, it meant subjects had Blood group O positive and the subjects whose Blood drops containing Antiserum D did not agglutinate in any condition given above then it meant, subjects had O negative blood group.

Project Designing

Consent was taken from the subjects to check their Blood group and then collected information by making a Questionnaire that either they like tea or not according to their Blood groups. Total of 138 subjects participated in the study. The subjects were students in Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan, Pakistan.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical Analysis was performed by using MS Excel.

Results and Discussion

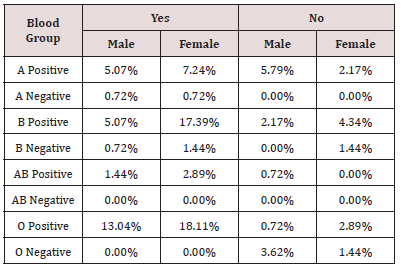

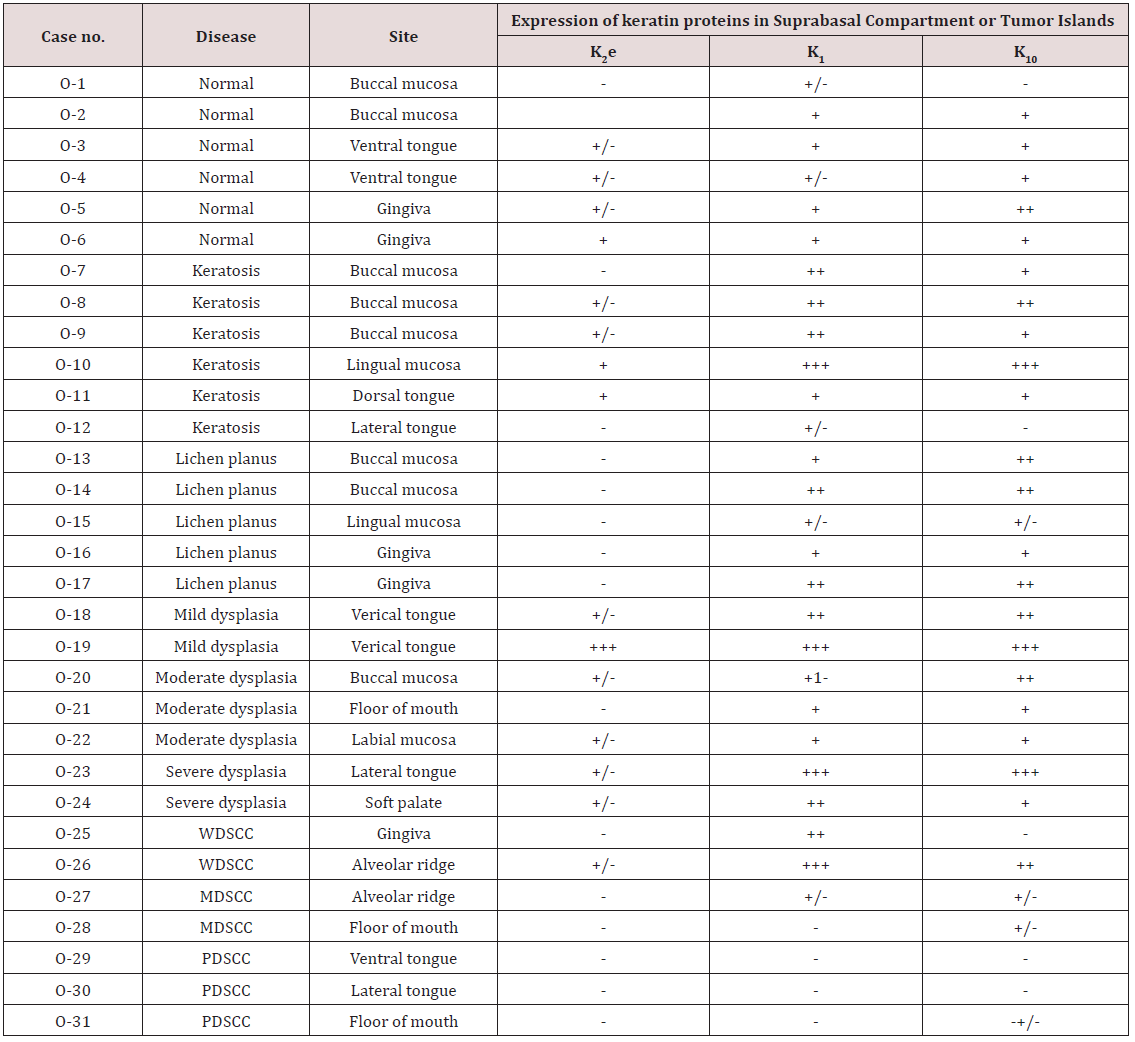

Questionnaire based studies have given an important advancement in recent researches [3-10]. Some researches like The Teas That Suits Your Blood Type by D’Adamo’s and Which Tea Is Good for You As Per Your Blood Group by Iram Zaz also gave us the information about the Association of Blood Group with Tea Likeliness (Table 1).

Conclusion

It was concluded from the present study that subjects (Female) having O Positive Blood group like tea very much while subjects having A Negative, B Negative and AB Negative Blood groups don’t like tea.

For more Lupine Publishers Open Access Journals Please visit our website:

https://lupinepublishers.blogspot.com/

For more Research and Reviews on Healthcare articles Please Click Here:https://lupinepublishers.com/research-and-reviews-journal/

Thursday, June 24, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| A Combined Material Substitutio...

Wednesday, June 23, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| Evaluation of the Performance o...

Tuesday, June 22, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| Combined Digital and Traditiona...

Monday, June 21, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | The Role of Chemotherapy in Tr...

Lupine Publishers| British Non-Regular Services Health Professional Veterans’ Perceptions of Pre-Deployment Military Advice for The Gulf War

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Health Research and Reviews

Abstract

Keywords: Gulf War (1991); Voluntary Services Health Professional Veterans; Military Advice; Pre-Deployment

Introduction

The Mobilisation of British Voluntary Services and Reserve Health Personnel

In November 1990, the `British Government recognised that there was an insufficient number of Regular Services medical personnel to meet the projected casualties from the impending war with Iraq, commonly known as the Gulf War (GW). Part- time Territorial Army (TA) and equivalent Voluntary Services’ (VS) personnel working in health professional roles (doctors, nurses, and other professions allied to medicine) were invited to volunteer [1]. As the initial response proved to be inadequate, retired ex Regular Services health professional personnel whose names had been retained by the military on the Reserve List were compulsorily called up: an action not undertaken since the Korean War (1950-53). Several United States (US) authors [2,3] report that for US Reservists, pre-deployment to the GW proved to be an unusually short time in which to make domestic preparations; wind-up civilian work-life; mobilise into new military groups and receive training specific to the requirements of deployment to a war in the Middle East. Some US Reservists were reported as being dissatisfied and distressed because they had not anticipated either their call-up or their stressful transition from ‘civilian to soldier’ [3]. These reactions could well have been similar for the British health professional veterans (HPVs) who like their US Reservist counterparts, lived and worked in civilian communities and not in military establishments [4,5]. Those in the part-time TA received support from their community-based parent TA Units but the ex- Regular Reservists both called up and volunteers, often had not retained military connections. In effect and despite being on the Reserve List, they were no longer part of the ‘military family’ [6].

The importance of giving support to military families prior to and during British and other nations’ military separations in peace and war has been emphasised by many authors prior to the GW, as a means of avoiding disruption to the psychological wellbeing of service personnel during deployment [7-10]. Early evidence of such support for British families during the GW was found only in one small British study by Quinault (1992) in which 12 wives of RAF deployed personnel described their military support as adequate but found that as with US military families [11], a lack of accurate information-giving increased their levels of stress [12]. There appears to be a paucity of early research concerned with the reactions of British non-regular Services health professional troops towards the GW’s unique conventional and expected unconventional (chemical/biological) warfare context and circumstances. In its place, it seems that there has been a reliance upon the outcomes of the more extensive early US GW research [13,14] to fill the British experiential gaps with the assumption that socially, organisationally and culturally, US troops were ‘like with like’ in relation to their British counterparts. Therefore, despite the time lapse since data collection and this article, it is believed that this study and its findings remain relevant. In response to the paucity of literature, this part of the study incorporated 4 questions:

a) What advice was received by the HPVs from the military?

b) In what form was it received?

c) How effective was it according to the perceptions of the HPVs?

d) What recommendations do the HPVs suggest that could improve advice during pre-deployment.

Methodology

Design

The study utilised a longitudinal design comprising an initial postal questionnaire survey and two follow up postal questionnaires, each issued six months apart. The first questionnaire sought retrospective experiential data comprising reactions to warrelated (pre-deployment and deployment) circumstances; advice; health; social support, and social and professional relationships in the six months before and in the first six months following the return home. The second and third questionnaires requested the provision of prospective repeated data at 12 months and at 18 months post war in the above key areas of interest where change could be anticipated.

Recruitment of the Participant Sample

Recruitment was conducted between July and August 1991 some 4-5 months after the non-regular Services’ troops return home from the GW. The first of three stages of the recruitment of the non-regular Service troops as study’s participants was initially opportunistic. One HPV Reserve called-up nurse (a colleague known to the lead author) held a personal contact list of 74 HPVs who had returned home together by air in late March 1991 following the end of the GW. As it would have been unethical for the researcher to have had direct access to the contact list, the colleague acted as an intermediary by forwarding a letter from the author to those named with details of the study and a pre-paid postal return envelope for the return of completed contact details and consent form. In the event, 57 (47 ex regular Reservists and 10 Territorial Army personnel) of the 74 HPVs agreed to participate in the study: a return rate of 77%. In the second recruitment stage, a purposeful increase of the VS TA group to match the size of the Stage 1 recruited Reservists (n=47) and in similar health professional roles was sought. This was achieved by asking the 10 consenting VS TA participants from Stage 1, to act as ‘intermediaries’ in making a ‘snowball’ access to similar others within their own or other TA units. To facilitate this, each of them was supplied with 5 introductory letters (n=50) with pre-paid return contact slips for direct return to the author. As a result, a further 33 TA HPVs agreed to participate in the study raising the total for the VS TA to 43. Although there was no way of knowing if the total number of letters (n=50) had been issued by the initial TA HPV participants, the estimated percentage (assuming all letters had been issued) for recruitment in this stage was 66%. Finally, in a third recruitment stage, a GW veteran Welfare Officer in the Order of St John of Jerusalem (a voluntary service that provides welfare support to the army) having heard of the study, made direct contact with the author to seek inclusion for the 10 Welfare Officers (WOs) who had been volunteers in the GW. Using the same return system as in previous stages, 5 (50%) of these veterans agreed to become participants. Personal, professional and military demographic characteristic variables (as independent variables) of the participant sample of 95 HPVs are given in Table 1.

Procedure

First a pilot study with 5 participant HPVs assisted the researcher through focus groups and interviews in the preparation of the first questionnaire that included the receipt and acceptability of advice from the military during pre-deployment. Each of the three questionnaires, issued at 6 monthly intervals, comprised closed questions followed by related free text justification. This dual approach provided opportunity for a greater depth of understanding more so than either could have achieved if employed alone [15]. The pilot study’s HPVs identified two forms of pre-deployment advice that they claimed to have received from the military:

a) advice for domestic preparations, e.g. wills, life insurance, work and domestic financial affairs, and

b) advice for managing social relationships at home and in the military.

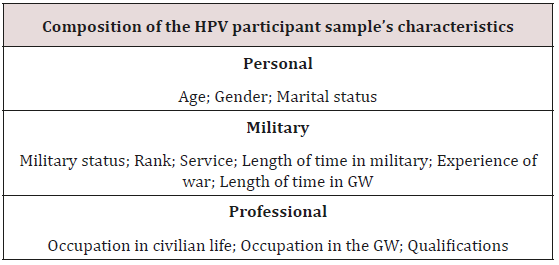

These form the focus of this article and coupled with demographic data given in Table 1, enabled the analysis of advice to be seen from personal, civilian and military perspectives.

Variables of Interest and Data Analysis

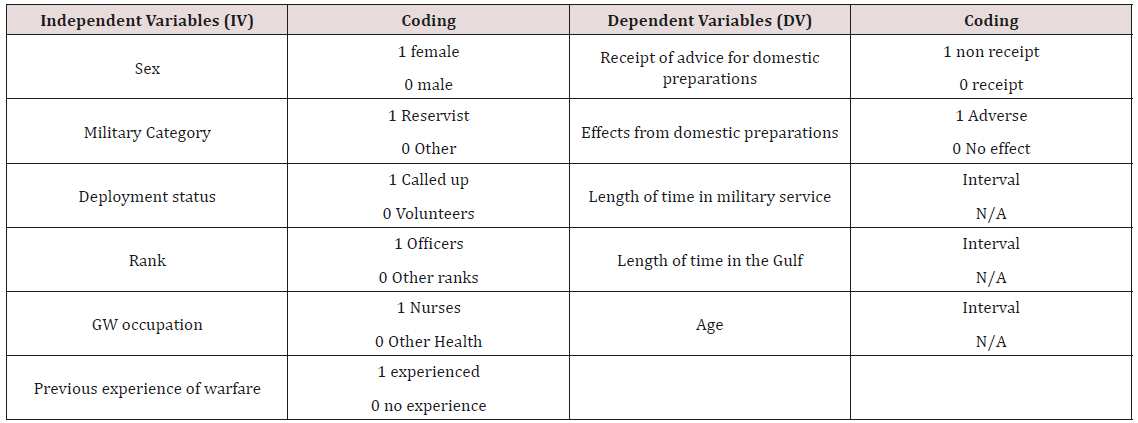

In 1993, the data were first analysed and then re-analysed in 2012 when presented as part of a successful PhD thesis. Quantitative data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 20. Logistic regression was employed to establish the relationship between a categorical dependent variable (DV) with one or more of the above characteristic independent variables (IV). It calculates the likelihood (ratio of the odds) of an event occurring or not. Table 2 provides the two types of variables and their values of interest (given as 1). Qualitative data were examined by two researchers independently identifying and categorising the key words or phrase labels using Thematic Analysis [16]. The labels were devised to capture as closely as possible the meaning of the HPVs’ original words or phrases [16,17]. Where there were differences of interpretation between the researchers, a joint reanalysis of the data was made to facilitate consensus.

Ethical Considerations

Although the study preceded the introduction of formal National ethical standards and procedures for British research, the general principles of: doing no harm; seeking participant informed consent; the acceptance of participant autonomy over compliance, and of respect for rights to privacy, anonymity and confidentiality [18] were upheld throughout the research process. Authoritative military and academic advice were taken before and throughout the study to avoid sensitive issues. All information forwarded to the HPVs cautioned them against breaching the Official Secrets Act. The data have been held securely and in accordance with the Data Protection Act, 1987 and its update in 1998. All data has been stored anonymously in digital format on a password-protected computer.

Results

Return Rate

A total of 134 contact letters were issued across the three recruitment stages resulting in 95 consenting HPVs and provided an estimated minimum overall response rate of 71%. It is of note that at the time of recruitment to the study, the total numbers of volunteer TA and Reserve personnel deployed to the GW had not been reported in the public domain but figures given some years after the GW suggest that the 95 HPVs in the participant sample represent a subset of some 9% of the total Reserve and TA (or similar VS organisations) health professional personnel sent to the GW [19].

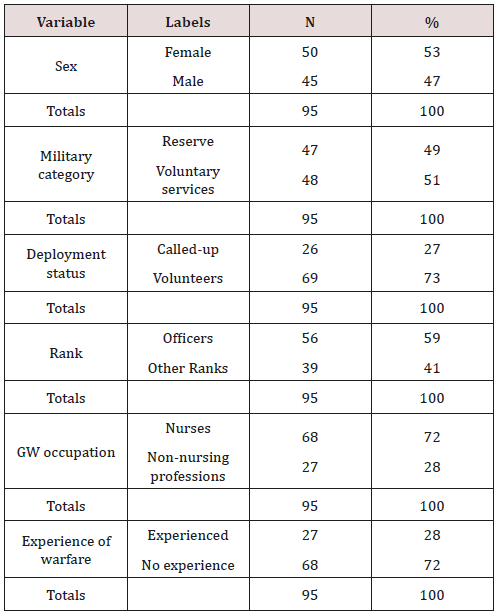

Characteristics of the Participant Sample

The personal, military and health professional details of the participants were collected. As shown in Table 3, there were 6% more females than males and the HPVs’ ages ranged from 23 to 53 years (mean=37; SD=8.59; median=35). Of the 48 in the Voluntary Services, all save the 5 Welfare Officers were in the Territorial Army [TA] and all were volunteers, whereas of the 47 in the Reserve, 26 (27%) were mandatorily called-up and the remaining 21 (21%) were volunteers. There were 18% more officers than those in other ranks. Sixty-eight (72%) of the HPVs were in nursing roles during the GW as compared with 27 (28%) in other health professions. Of the 95 HPVs, 27 (28%) had past warfare experience and of these, 17 (18%) were ex Regular Reservists and 10 (10%) were in the TA. The remaining 68 (72%) had no experience of warfare. Sixtyseven of the 68 nurses provided their civilian nursing qualifications (1 missing) and during the GW, 49 (73%) worked as Registered General Nurses; 4 (6%) as Registered Mental Nurses, and the remaining 14 (21%) were State Enrolled Nurses. All other health professionals (doctors, physiotherapists, etc.) were allocated to the same professional roles in the military as they held in civilian life. Only combat medical technicians (akin to civilian ambulance paramedics) worked in non-health civilian roles prior to the GW. The time spent in the Gulf for most HPVs was between 2 and 3 months. When the HPVs’ length of time in the Gulf was compared with their deployment military status using a Mann-Whitney U test, Reservists spent less time in deployment (mean rank=37.16) than those in the VS (mean rank = 58.61): a significant difference (U=618.500, Z= -2.414, p<0.01).

Types of Advice

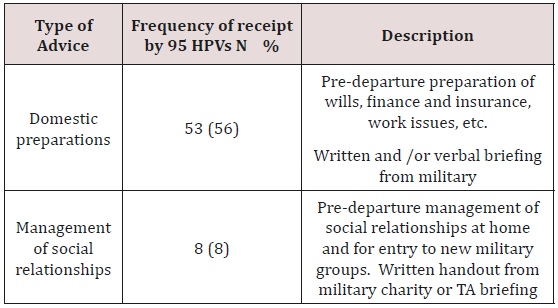

Table 4: Types of advice suggested in the Pilot Study as issued by the British military during pre-deployment (N=95).

The Pilot Study participants identified two forms of advice given by the military and/ or by related charities during pre-deployment to the GW with their respective frequencies of receipt by the 95 HPV participants, as shown in Table 4. ‘Advice for domestic preparations was the most frequently received form of advice (56%), whereas the receipt of advice regarding social relationships was considerably lower (8%). Both forms of advice were given in a written format and in the case of those in the TA, also in verbal briefings.

Frequency of Receipt of Advice for Pre-Deployment Domestic Preparations

Fifty-three of the 95 HPVs (56%) received advice from the military regarding their domestic preparations. Eight HPVs provided related descriptive comments and of these, five were in the TA. As shown in Table 5, Theme 1, those in the TA confidently recounted that their domestic affairs had already been adequately prepared as a routine annual requirement for all members of the part-time VS military and as such did not seem to need the advice. Of the remaining 42 (44%) participants who did not receive this form of advice, 33 provided written comments hypothesising on the effect such advice might have had if it had been received. Comments from the 33 non-recipients of advice for domestic preparations are given as Themes 2 and 3 in Table 5. In theme 2, some HPVs associated their non-receipt of advice with not having enough time between mobilisation and departure to the Gulf in which to access or put advice into practical use. It is also suggested that the timing of such preparations (during the run-up to Christmas 1990) had a negative effect upon their stress levels even before departure to the Gulf as they tried to juggle home commitments with military requirements. Furthermore, some Reservists called-up emphasised that they had civilian responsibilities that required additional attention (e.g. rearranging care for dependent relatives, arranging work cover if self-employed) but the military were perceived as making little or no allowances for these issues. As indicated in the last comments in Table 5, the making of wills raised the HPVs’ consciousness of the gravity of their situation and its potential for life-threat (injury or death). This was likely to have been particularly difficult for Reservists call-up, who had no choice in having to place their lives at risk.

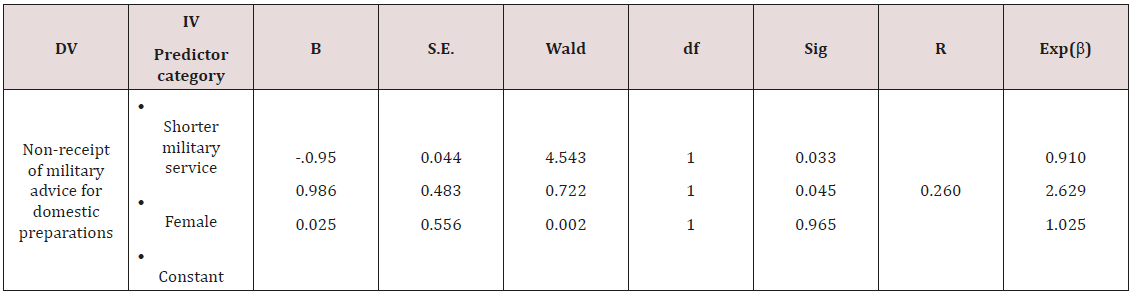

Predicting the likelihood of Non-Receipt of Military Advice for Domestic Preparations

Table 6: Logistic regression to predict the likelihood of non-receipt of military advice for domestic preparations with sample characteristics (N=95).

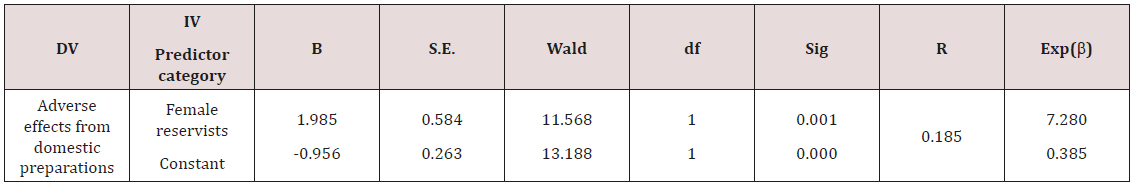

Using logistic regression as shown in Table 6, ‘time in military service’ (shorter time) and gender (females) were the best predictors of the ‘non-receipt of advice’. When both variables were re-entered into the Logistic regression model as the interaction term ‘gender/time in the military’, the output was not significant. Thus, those who were female and those with a shorter length of military service each had a significant and independent likelihood of being the non-recipients of advice (shorter military service R=0.260, β=0-910, p=0.033; female R=0.260, β=0.0986, p=0.045). When the 95 HPVs were asked to indicate if they had experienced any effects (practical or psychological) from undertaking domestic preparations, 34 (36%) HPVs described experiencing ‘adverse’ effects and 57 (60%) stated that they had ‘no effects’. The remaining 4 (4%) HPVs perceived these effects as ‘positive’ indicating a sense of relief at having made adequate provision for themselves and their families (in some cases, will-making was a task that had been put off in the past). Of those with adverse effects, a majority (28:82%) provided written comments indicating that making their wills heightened a morbid anticipatory fear about going to war. As shown in Table 7, using logistic regression to predict those most likely to have adverse effects from domestic preparations, a significant interaction between gender and military status indicated that female reservists were those most likely to have adverse effects (R=0.185, β=7-280, p=0.001). Using chi-square, no significant relationship was found between those in receipt of advice for domestic preparations with those with adverse effects arising from undertaking such preparations (χ2 =0.33, df=1, p>0.05).

Table 7: Logistic regression to predict the likelihood or not of effects from domestic preparations in sample characteristics (N=91).

*4 values excluded

Receipt of Pre-deployment Military Advice Regarding the Management of Social Relationships

Four TA respondents commented that they had received good advice from their TA Unit in the form of a ‘briefing’ for the management of their social relationships prior to departure to the Gulf. A further 4 Reservists stated that they had been recipients of handouts from military charities such as Soldiers, Sailors, Air Force Association (SSAFA) but had received nothing directly from the military. The remaining 87 (92%) stated that this type off advice had not been received. Thirty-two HPVs provided related comments. Of these, 8 had received advice and 24 were from non-recipients, who speculated upon the potential usefulness of such advice had they received it. Examples drawn from both sets of comments are given below in Table 8 under thematic headings. Thematic analysis of the 24 non-recipient HPVs’ comments given in Table 8 revealed that all participants believed hypothetically that if they had received advice on how to manage their social relationships, it could have been beneficial. Those with close partners (Theme 3) suggested that such advice could have lessened their tendency towards selfcentredness and withdrawal which caused spousal resentment and upset with other family members prior to departure. Other HPVs hypothesised that the receipt of this advice could have been beneficial in their coping with the relationship difficulties that arose when joining new military groups both during pre-deployment training and following arrival in the Gulf (Theme 4).

HPVs’ Recommendations to Improve Advice During Pre-deployment

Ninety-seven recommendations were given by 81 (85%) of the 95 HPVs, regarding improvements to all aspects of the experience of pre-deployment to war. Of these, the most frequently suggested recommendation by 48 (59%) of the 81 HPVs) was to improve advice for domestic preparations. Of these, three themes were formed as given in Table 9. In theme 1, some HPVs recommended that they should be pre-warned regarding the reality of the war that lay ahead as part of their preparations and most wanted this to be delivered by an experienced war veteran. Others (theme 2) wanted written information listing the practical domestic requirements to be met before departure as described above but they also included a direct military contact via letter to partners explaining why the non-regular health professionals had been requested to volunteer or had been called up. The final theme addressed the psychosocial issue of entry to new groups and recommended being forewarned of the likelihood of inter-group difficulties and how to manage these. The remaining 14 (15%) said that ‘no improvements were necessary’.

Discussion

The study aimed to describe the frequency of receipt of the two forms of advice received during pre- deployment by the HPVs, how they were accessed and their perceived quality and usefulness. The small number of VS TA recipients of pre-deployment advice for domestic preparations accessed it through their units with delivery from personnel with experience of participation in previous wars. As such, there appears to have been dissemination of verbal and written advice concerning these TA preparations. From the comments, the TA HPVs appear to have had their domestic preparations well in hand as a requirement for their military routine preparations for annual exercises. As they appeared to regard their upkeep as a personal responsibility rather than a pressure from the military, this might suggest that they had adopted a problem-focussed coping strategy towards domestic preparations rather than the emotion-focussed coping strategy apparent in the comments from some Reservists. Meredith [20] contend that by adopting the first approach, it is likely that the sense of internal control and resilience to stress could increase [21]. The above findings are akin to other published findings from this study showing that the TA HPVs were more satisfied with their pre-deployment training for the GW than their Reservist counterparts [22].

The non-receipt of pre-deployment advice for domestic preparations was associated independently with the HPVs who were female and those with a shorter military service. One tentative explanation for this gender effect could lie in the observed unequal distribution in civilian life in the undertaking of housework workload where the greater share is more likely to be undertaken by females rather than males [23]. Conversely males tend to attend to matters of family finances. These factors, coupled with the additional family pressures associated with the festive season at the end of 1990, may have led a significant number of females to become overwhelmed by the enormity of juggling personal, family and military tasks in the short pre-deployment time. Females were the most likely non-recipients of advice for their domestic affairs, but female Reservists were those most likely to have reported adverse stress effects from undertaking them. The latter took the form of anticipatory morbid thoughts of death and injury when making wills or taking out new or additional insurance. It seems plausible that the lack of adverse effects from domestic preparations in VS TA females could have been influenced by their close alignment with males through shared military training and roles; mutual commitment to the TA’s organisational requirements, and their self-confidence in having relatively unproblematic and in-place preparations. Additionally, Wood [24] suggest that females can learn male dominance behaviours through shared training, which in turn can lead to greater gender equality [24].

In this study, those with a shorter military service were more likely to have had less advice for domestic preparations than those with a longer service. This is not dissimilar to the findings of McCubbin [25] who found that younger service personnel (i.e., by default, those who are the most likely to have a shorter military service experience) were those who tended to avoid formal and informal advice. Case [26] in reviewing the knowledge-base for people’s assessment of threat report that the uptake of information is determined by the nature of the stressor, the would-be recipient’s appreciation of the effectiveness of responses to the threat (response efficacy), and their beliefs about their own ability to carry out effective responses (self-efficacy) [26]. Thus, it seems that HPVs with shorter service time could have had less anticipatory understanding about warfare; less recourse to war-related advice, and less belief that such advice could make a difference to their actions. For them, advice could have seemed irrelevant. In a study of US females deployed to the more recent Iraq and Afghanistan wars, Carter-Visscher [27] reported that females perceived themselves as having a lower level of preparedness for deployment and exhibited greater pre-deployment concerns about family than males [27]. These findings re-echo some of the present study’s gender findings, despite differences in sampling, military structures and cultures.

Pincus [28] notes that as the military person becomes more involved with military preparations for deployment so too is there a gradual withdrawal from family up to the date of departure [28]. Although the importance of the provision of military support to families prior to and during the time of military separation has been emphasised by many authors before the GW [7-10], there is little evidence of any prioritisation for the issue of British military advice for managing social relationships before departure to the GW. Less than ten per cent of the HPVs received advice for the management of their social relationships prior to departure (even though the pilot study respondents raised it as an available form of military advice). However, had it been received, the non-recipient HPVs believed that the pre-departure strain on family relationships, arising all be it understandably from the HPVs’ self-confessed war-focused attitudes since call-up, could have been eased. Others hypothesised that had it been received, it could have reduced the inter-personal tensions reported in other parts of this study concerned with the HPVs’ entry into new military groups during pre-deployment and later during deployment. The paucity of such advice could be of relevance to other published data from this study whereby it has been suggested that the HPVs’ lack of stress management training from the military during pre-deployment [22] showed a tendency towards avoidance by the military of issues that were perceived to be of ‘psychosocial’ origins.

It is not possible from these data to quantify whether the receipt or not of either form of advice is related to: its availability from the military; the ability and desire of the individual to access it; the receptiveness of the individual’s open or closed mind towards its content; avoidance or denial of its context, or anticipation of its relevance to a given situation [29]. For these, further research with the close co-operation of the military would be necessary. Certainly, as the receipt or not by the HPVs of advice for domestic preparations was not significantly associated with its effects, this could suggest that even when there was receipt of this form of advice, it did not appear to act as a stress moderator, as previously reported in a study of the receipt of health care advice [30]. Furthermore, in comparative research by Sharpley [31], no evidence was found that military pre-deployment stress briefings reduced psychological stress [31]. It could be argued that advice for social relationships from any source was so low that it is impossible to determine its therapeutic value, but the HPVs’ recommendations were clear that more effort should be made by the military to target audiences where there is likely to be the most need; and that the form of the advice (content, presentation), and logistics (its timing) are tailored to meet the reality of their needs.

Limitations

The study in its entirety is believed to be one of the earliest of the British GW studies and although some 28 years have passed since the War’s end and the study’s data collections began, interest in the GW and its unique circumstances (including the unresolved illness in some veteran troops) has not waned. Indeed, unlike this study, many British Gulf War studies have been based upon data collected not months but many years after the GW. Such lengthy delays have been recognised as raising the possibility of increasing error in participants’ recall [32,33]. As with many studies that seek to explore, describe and explain unforeseen life events (and including aspects of warfare), the ideal of representative samples and controls before, during and after such events [34] was neither feasible nor realistic for the present study. It is acknowledged that the non-random sample selection could have caused bias but it is believed that the efforts to ‘engineer’ the same-subject sample with participant representation in the key military dimensions of military category (Reserve/ VS), deployment category (called up/ volunteer) and GW occupation (nurses/ CMTS/ other health professionals), go some way towards lessening this potential effect. It can also be suggested that the study’s reliability is strengthened by the high ‘acceptance to participate’ of the HPVs (71%) and the high HPV participation retention level (90.5%) across the 18 months of the duration of the study.

Conclusions

Although those in the TA were comparatively well organised for the GW due to their annual domestic preparations for military exercises, this was not the case for some of the female Reservists who qualitatively showed morbid stress responses to their preparations. Overall females and those with a shorter military service were the least likely to have received this form of advice. Advice for the management of social relationships with families and with new military groups during the pre-deployment phase did not appear to have been recognised by the military as areas where advice could be useful. In contrast, veterans were clear in their recommendations as to how future need for advice for these social relationship’s difficulties could be met. We suggest that listening to the voices of those who have experienced warfare can better support the development of advice with relevant content and an efficacious mode of delivery in the future. By doing so, some of the stress of pre-deployment could be reduced.

For more Lupine Publishers Open Access Journals Please visit our website:

https://lupinepublishers.blogspot.com/

For more Research and Reviews on Healthcare articles Please Click Here:https://lupinepublishers.com/research-and-reviews-journal/

Friday, June 18, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | The Consciousness in Health-Di...

Thursday, June 17, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| Assessment of Genetic Mutations...

Wednesday, June 16, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| In Pursuit of Privacy: An Intro...

Tuesday, June 15, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| In Pursuit of Privacy: An Intro...

Monday, June 14, 2021

Lupine Publishers| Keratin

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Health Research and Reviews

Abstract

Eating foods high in protein gives the body the amino acids it needs to make keratin. Red meat, fish, chicken, pork, eggs, milk and yogurt all protein rich. The best plant sources of protein include beans, nut, Nat butters and quinoa. Most adults need two to three servings of protein each day to meet their daily requirements. Keratin is more of a restorative treatment borday says “Elen if you have a good hair type, it still strengthens the hair shaft and makes your hair mover salient. Sadock recommends checking with a demonologist before getting a keratin treatment if you have protasis or seborrheic dermatitis (Figure 1).

Keywords: Foods; Protein; Nut Butters; Strengthens; Keratin

Introduction

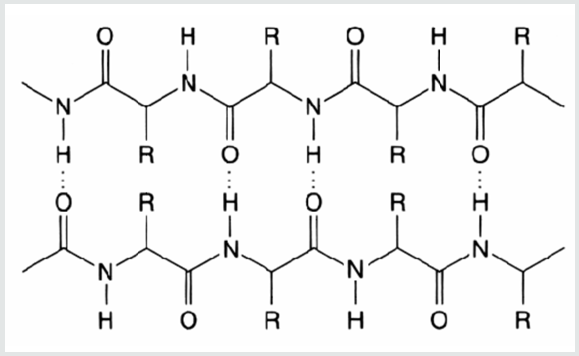

“Keratin treatment” has become the term of choice for hair- smoothing processes that leave your hair frizz-free for weeks (even months) but forget about the word keratin. “It’s just a make ting buzz word – it’s not doing anything to smooth the hair”, first, a quick chemistry lesson. Think of straight hair as a lader and curly hair as a spiral staircase. The steps on both are the hair’s bonds. If you break those bonds, you can rebuild the spiral stair case as ladder so curly hair becomes straight. Ammonium thiol collate and sodium hydroxide permanently break the bonds that’s how traditional relaxers and “jopynose straightening” treatments transform the texture of the hair, “these treatments last until your hair grows out, bat they can be damaging, say schaeller. (And they will subject you to a very awkward growing-out phase.) some “keratin treatment” (and the popular brozillinbleu out original solution) saturate the hair with of onal dehyde solution before its dried and flat ironed; the format dehyde (yes, it’s a suspected cancer gen for human) looks the hair into that straighter positions. Its stays smooth beyond your next shampoo. Your natural texture then gradually returns over two five months.

Materials and Methods

Keratin treatments won’t make your hair break, but the flatironing might. “The hair breakage has nothing to do with the treatments and everything to do with the flat irons that are used to dry and seal the hair a fleruard”, some stylists may use a flat iron that is way too hot and scorches hair making it break off”. Think of straight hair as a ladder and curly hair as a spiral staircase. The steps on both are the hair’s bonds. If you break those bonds. You can rebuild the spiral staircase as ladder-so curly hair becomes straight. No hair treatment will technically contain formaldehyde (because a little more chemistry you it’s a gas). What they are able contain are methylene glycol, formalin, methanol, and methane did – ingredients that release formaldehyde when heated or mixed with water. Several new hairs-smoothing treatments use glyoxylic acid (or a derivative of it) to lock the hair into a straighter position. Results don’t usually last more than two or three months and these treatments won’t dramatically soften your curl pattern the way formaldehyde solution can.

Biotin-Rich Foods

Biotin is needed to metabolize the amino acids that create keratin and is generally recommended to strengthen hair and nails. Dietary sources of biotin contain nut, beans, wholegrains, caul flower and mushrooms.

Foods with Vitamin A

Vitamin A is needed for keratin synthesis good dietary sources of vitamin A contain orange fruits and vegetables like pumpkin, sweet potatoes, butternut squash, raw carrots and cantaloupe. Kedgerees like spinach, kale and collards are also high in vitamin A. Boost your hair, nails and skin from within care for your precious hair by eating the right vitamins and foods that increase keratin production. Included is knowledge on why keratin is important and which foods and vitamins will offer the best support.

Increasing Keratin Production

a. Fruit and vegetable: It aren’t a surprise that increase keratin production include fruits and veggies. Produce that orange, such as mangoes, carrots, sweet potatoes, and cantaloupe are high in carotene, which helps your body produce keratin. Carotene can also found in spinach, green peppers and squash.

b. Meat and dairy: Iron-rich protein can boost the production of keratin in the body and improve the health of skin, hair and nails, liver, fish and lean meats build keratin in your body.

c. Iron rich foods: Iron-rich animal protein includes turkey, duck, chicken, pork, shrimp, eggs, lean beef and lamb. Plant foods that contain iron-rich protein include beans, spinach, black-eyed peas, soybeans, to fuand lenticls.

d. Vitamin C: foods rich in vitamin C include brocade, frazzles sprouts, kale, peppers, guava, papaya, grape fruit, oranges, pine apples, strawberries and lemons.

e. B vitamins: Foods with folate include a meal, fortified whole grain cereal, spinach, beets, parsnips, broccoli, okra, black-eye peas and soybeans.

f. Zinc: Consume foods with zinc, such as asters, crab, pork, ronde lain, turkey, veal, chicken, peanut butter, wheatgerm and chick peas.

Result and Discussion

Keratin treatments won’t make your hair break, but the flat-ironing might. No Nair treatment with technically contain formaldehyde (because - a little more chemistry you it’s a gas). Results don’t usually last more than two- or three-month biotin contain nut, beans, wholegrains, cauliflower and mushrooms. Vitamin A contain orange fruits and vegetables.

a. Like pumpkin, sweet potatoes.

b. Fruit vegetables

c. Spinach, green peppers and squash.

d. Meat and dour: liver, fish and lean meats build keratin in body.

e. Iron: beans, spinach, black-eyed peas, soybeans, tufa and lentils.

f. Vitamin C: include: broccoli, brussels sprouts kale, peppers, guava, papaya.

g. B vitamin: broccoli, okra, black-eye peas and soybeans.

h. Zink: turkey, veal, chicken, peanut, wheatgerm and chick peas.

Acknowledgement

I am thanking of my mother and father that support me. And news agency (Mehri, Fars, Isnad, Iran, Mojo, mina) and (Aftab- Yazd, redeemer, Khorasan) that published my subject science. And journal healthy house plant (Mrs. Julie Boudin Davis. of Dr. Alfred French and thanks that accepted my abstract for meeting. Of Prof. Hermann Hege am thanks that my subject used on university kiel Germany. Of kew garden (UK) am thanks that every month send your newsletter.

On finish of aces that every day send abstract journal and I was support to (Figure 2) and (Table 1).

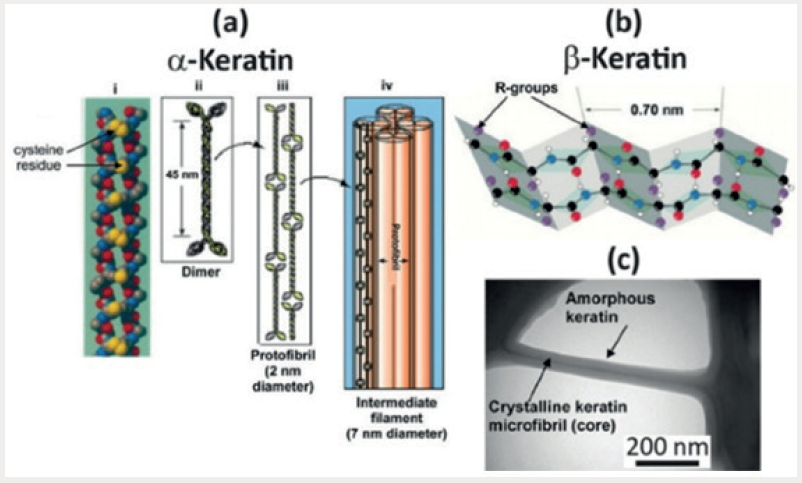

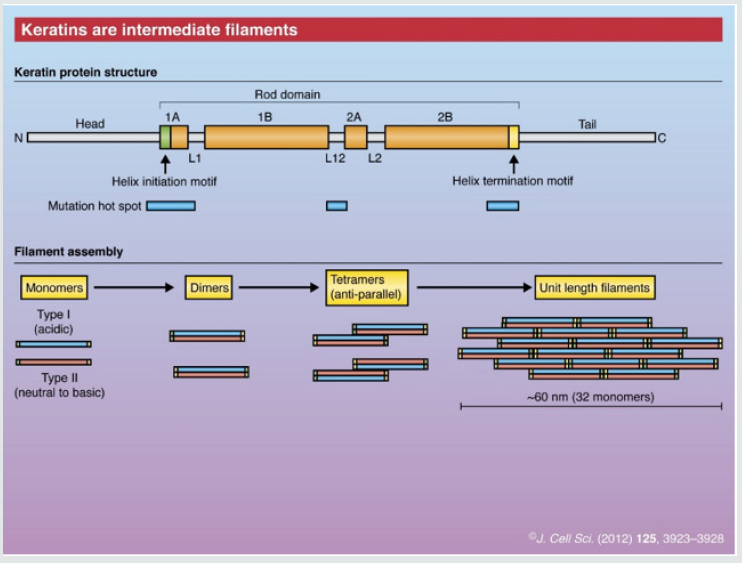

Aspergillus Niger is one of the most important microorganisms in biotechnology. It has been already used to produce extracellular enzymes such as glucose oxidase, pectinase, α-amylase and glucoamylase, organic acids, and recombinant proteins. In addition, A. Niger is used for bio transformations and waste treatment [1-3]. Among the various enzymes produced by the fungus are included proteases. The major extracellular proteolytic activities in A. Niger appear to be due to acid proteases [4]. Acid proteases [E.C.3.4.23] are endopeptidases that depend on aspartic acid residues for their catalytic activity and show maximal activity at low ph. These enzymes offer a variety of applications in the food, beverage industry, and medicine [5]. Keratin is a fibrous protein that occurs in vertebrates and exerts protective and structural functions. It is the major component of feathers, wool, scales, hair, stratum corneum, horns, scalps, and nails [6]. Keratin is insoluble and presents high mechanic resistance, as well as recalcitrance to common proteolytic enzymes like pepsin, trypsin, and papain [7]. This resistance is because of the tight folding of protein chain in α-helix (α-keratin) and β-sheets (β-keratin) in a super-coiled polypeptide chain, kept by strong association by disulfide bonds [8,9]. Keratinases [EC 3.4.21/24/99.11] are specific proteases that display the capability of keratin degradation. These enzymes are gaining importance in the last years, with many applications associated with hydrolysis of keratinous substrates, mainly byproducts of agroindustry processes [10]. Generally, keratinases have optimum pH from neutral to alkaline [11]. The utilization of agroindustry wastes may represent an added value to the industry and meets the increasing awareness for energy conserving and recycling [12]. This fact stimulates the investigation for alternatives to convert keratinous waste into valuable products [10]. One example is the poultry industry that generates huge number of byproducts, which may represent a potential environmental hazard if they are incorrectly destined or processed. The processing and/ or treatment of slaughterhouse waste have been one of the great concerns of poultry industry, mainly because of the restrictions on environmental questions [13]. In this work, the production of proteolytic enzymes by a new keratinolytic strain of A. Niger was investigated. The enzyme activity was partially characterized, and a culture medium based on keratinous substrate was selected, evaluating the influence of growth substrate concentration and medium pH on the production of proteolytic enzymes (Figure 3).

For more Lupine Publishers Open Access Journals Please visit our website:

https://lupinepublishers.blogspot.com/

For more Research and Reviews on Healthcare articles Please Click Here:https://lupinepublishers.com/research-and-reviews-journal/

Friday, June 11, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Main Components of Liquid Biop...

Thursday, June 10, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| Reversal of Rocuronium-Induced ...

Wednesday, June 9, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| Non-Surgical Pneumoperitoneum C...

Tuesday, June 8, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| Processing and Analysis of Larg...

Friday, June 4, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Ganglion Impar Pulsed Radiofre...

Thursday, June 3, 2021

Lupine Publishers Pedaitrics and Neonatology: Lupine Publishers| Late Intrahospital Bath Is Safe...

Wednesday, June 2, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| Orthopedics and Sports Medicin...

Tuesday, June 1, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| Nocuous Skin Manifestations of ...

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| A Standard Pediatric Dental Clinic

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| A Standard Pediatric Dental Clinic : Lupine Publishers| Journal of Dentistry and Oral Health Care Aft...

-

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Health Research and Reviews Abstract Metabolism is the process your body uses to make energy f...

-

Heat wave killings in Pakistan and possiblestrategies to prevent the future heat wave fatalities by Syed Zawar Shah in Research and ...

-

To Examine the Relationship and Strength of Alcohol-Related Intimate Partner Violence in sub-Saharan Africa by Ekpenyong MS in Rese...