Lupine Publishers Journal of Surgery and Journal of Case Studies: Currently case studies drag the concentration of the investigators since each case present provides deep understanding in diagnosis and treatment methods. It is devoted to publishing case series and case reports. Articles must be genuine

Wednesday, March 31, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| Integration of Novel Emerging T...

Tuesday, March 30, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| Model Selection in Regression: ...

Monday, March 29, 2021

Lupine Publishers| Pseudo-Infarction Patterns Leading to Undue Thrombolysis

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Health Research and Reviews

Abstract

Background: Acute ST elevation Myocardial Infarction (MI) is a life-threatening emergency, recognized on Electrocardiogram as ST Elevation requiring urgent management in the form of reperfusion therapy. There are some other causes of ST elevation as well, that are needed to be kept in mind before giving reperfusion therapy to only to true ischemic events. This study was carried out to look for the pseudo-infarction patterns leading to undue delivery of thrombolytic therapy.

Methods: A retrospective study was done. All patients suspected of ST elevation MI given thrombolytic therapy were analyzed, with cardiac enzymes and echocardiography (ECHO), that whether the event was truly ischemic or they were unduly diagnosed and treated as infarction.

Results: There are few causes of pseudo ST Elevation that are to be looked for before giving thrombolytic therapy in suspected ST elevation MI.

Conclusion: Every ST Elevation is not an infarction so a careful approach is required to rule in and rule out infarction in emergency room.

Keywords: ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction; Pseudo-infarction; Reperfusion

Abbreviations: MI: Myocardial Infarction; STEMI: ST Elevation myocardial infarction; ECHO: Echocardiography; LBBB: Left Bundle Branch Block; LVH: Left ventricular Hypertrophy; ERP: Early repolarization pattern; ECG: Electrocardiogram; WPW: Wolf Parkinson White; STE: ST elevation; ERP: Early repolarization syndrome; ACS: acute coronary syndrome

Introduction

Acute ST Elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) constitutes a major chunk of the health problem in public sector not only in western countries but also increasing in developing countries as well [1]. In United States, the cerebrovascular events are estimated to be more than half a million annually and these have urged strong desire not only to increase in the need of health care delivery but also the importance of better providence of management therapies. [2-4]. Acute MI due to a thrombus causing vessel occlusion is recognized on Electrocardiogram (ECG) by ST elevation [3]. Early (60 to 90) and complete patency of the infarct-related artery determines the chances of survival after acute myocardial infarction [5-7].

Reperfusion therapy, either thrombolytic or primary angioplasty, is the way to get the patency back and is known to be beneficial in such cases. Time is myocardium so earlier the achievement of flow in the vessel by reperfusion therapy, the better the chances of survival and less incidence of morbidity and mortality. Thrombolysis is the established treatment in the early management of myocardial infarction and it reduces 35 day mortality by about 25% [8]. In developing countries, where thrombolytic therapy is still the most carried out treatment than primary PCI, it is important to keep in mind that acute infarction is not the sole cause of ST elevation and similar changes of ST Elevation can be seen in patients with nonobstructive coronary artery disease meaning by having pseudoinfarction patterns [9].

Methods

Patients presenting in the emergency department of JHL during the month of July, 2017 to July, 2018 with chest pain and ST elevation in two contagious leads, thrombolysed with streptokinase on standard protocol were retrospectively analyzed. There data including the serial ECGs done on daily basis during their hospital stay for evolutionary changes, two sets of cardiac enzymes (Troponin I) for rise and fall pattern, Echocardiography (ECHO) done on 3rd or 4th post admission day for regional wall motion abnormalities, and coronary angiography within 5 days for evaluation of coronary anatomy, culprit lesion assessment and further intervention, were evaluated to confirm the true occurrence of cardiac ischemic event. The Study was approved from the ethical board review of the institution. Data was analyzed in SPSS version 22.

Results

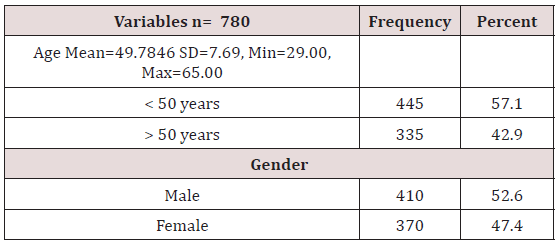

Age distribution of the patients was done which shows that 57.1% (n = 445) were less than 50 years of age while 42.9% (n = 335) were above 60 years of age, mean ± SD was calculated as 49.78 ± 7.69 years (Table 1).

Patients were distributed according to gender showing that 52.6% (n = 410) were male while 47.4% (n = 370) were female (Table 1). The mean hospital stay of the patients was 5±1 day. Among these patients 59% were of suspected anterior wall MI, 7% of inferior wall MI, 33% of inferior wall MI with RV infarct and only 01% isolated posterior wall MI. Doing analysis with the help of various modalities like ECG, ECHO, Angiography, Cardiac enzymes, total 83 (10.64%) out of 780 patients were found to be having pseudo-infarction pattern, not fulfilling the criteria of having acute ischemic event receiving thrombolytic therapy.

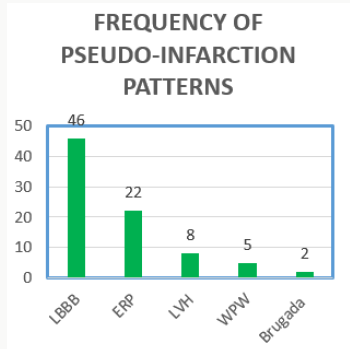

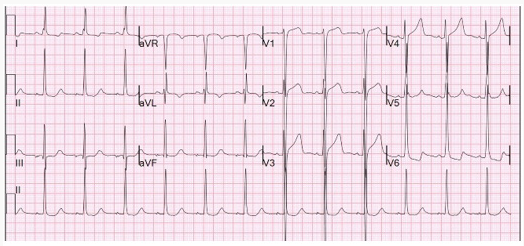

Following were the patterns with decreasing frequency: (Figure 1)

i. Left bundle branch block (LBBB) 55% (n=46)

ii. Early repolarisation therapy (ERP) 26.5% (n=22)

iii. Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) 9.63% (n=08)

iv. Wolf-parkinson-White pattern (WPW) 6.02% (n=05)

v. Brugada Syndrome 2.40% (n=02)

All 780 patients were given thrombolytic therapy with success except for three patients who became hypotensive and were not completely given thrombolytics. The mean time for SK administration was 47+-5 minutes.

Discussion

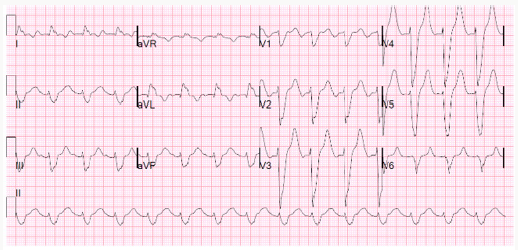

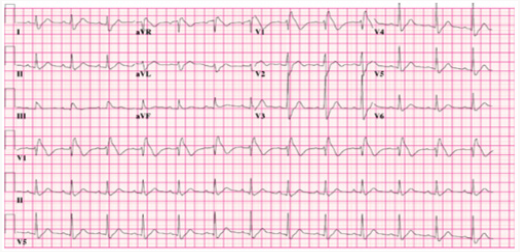

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction consider the presence of electrocardiographic ST segment elevation of >0.1 mV in two anatomically contiguous leads as a class I indication for urgent reperfusion therapy in the patient presumed to have Acute Myocardial Infarction (MI). There are several other causes of ST elevation apart from MI which have close resemblance to the ST elevation of infarction pattern like Left Bundle Branch Block (LBBB), Left ventricular Hypertrophy (LVH), Early repolarization pattern (ERP), Brugada Syndrome, Male ECG Pattern, Wolf Parkinson White (WPW) syndrome, Hyperkalemia, Pericarditis, etc [10]. These patterns are misinterpreted as acute infarction and sometimes given undue thrombolytic therapy. Elevation of the ST segment due to non-ischemic etiologies was reported up to 15% in the general population. Goldberger et al [11] through his study showed that the LBBB pattern is one of the most commonly misinterpreted pseudo-infarct pattern encountered in emergency room, resulting in inappropriate treatment. Of the patients with LBBB having STEMI protocol initiation, only 39% had a final diagnosis of actual ACS, 36% do turned out to have cardiac diagnoses but other than ACS which may be hypertensive emergency, acute heart failure, atrial fibrillation, severe aortic stenosis, etc. and 25% had non-cardiac diagnosis [10,11] (Figure 2).

The LBBB causes significant changes in the depolarization and repolarization masking the acute changes caused by infarction. There are number of proposed criteria’s which help in the differentiation of acute LBBB due to acute ischemia/infarction. Sgarbossa et al [13] proposed an algorithm based on ST-segment changes having a sensitivity of 78% and a specificity of 90% for the diagnosis of MI. The criteria comprises of three points including ≥ 0.1 mV of concordant ST elevation (STE) or ≥ 0.1 mV ST depression in leads V1 to V3 with discordant STE ≥ 0.5 mV in leads while smith and colleagues [14] found replacing the third criteria of > 5mm absolute deviation in leads with discordant QRS complex with an ST/S ratio ≤ -0.25 increasing the sensitivity to around 91% keeping specificity same. Our study also confirms the same results showing LBBB prevalence to be 55%, making the most common pseudo-infarction pattern, leading to a diagnostic dilemma for emergency physicians in making correct diagnosis. The second most common cause in our study for undue activation of thrombolytic protocol came out to be Early repolarization syndrome (ERP). It has been called by a variety of names including “unusual RT Segment deviation”, “premature repolarisation“, normal RS-T elevation variant”, and “early repolarisation syndrome” [15]. The “early repolarization” pattern is usually found 1% to 5% in the population [16-17] most commonly found in young, athletic, black males [15,18] but this distribution is not rare in women, older persons, whites and inactive persons [15]. The mechanism of early repolarisation is not completely understood; although accumulating evidence suggests a vagal origin [16,19]. In the past, early repolarization pattern was considered a benign pattern [18] but now it has its own association with cardiac morbidity and mortality. Even then the presence of ERP doesn’t warrant administration of thrombolytic therapy (Figure 3).

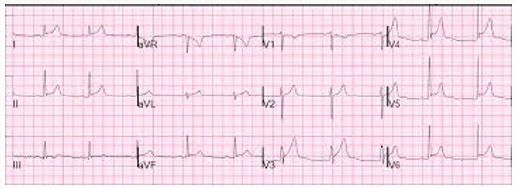

It is diagnosed when there is no S wave in V3; Concave STsegment elevation of 1-4 mm in leads V2-V5 (most prominent in V3) and may be in inferior leads; and notching of the down-stroke of the R waves (“J” wave), most prominent in lead V5 and V6 [15]. Additional ECG criteria for the ERP include reciprocal ST segment elevation in AVR and waxing and waning of the ST Segment over time [20]. Early repolarisation of the ST segment is an electrocardiographic variant with a benign long-term prognosis [15]. Larsen et al. [21] have shown that hypertrophy of the left ventricle (LVH) is incorrectly interpreted more than 70% of the time in patients thought to have an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Failure to make this diagnosis is responsible for large financial payments in the medico legal arena involving malpractice cases against emergency physicians [22-23]. Retrospective analysis of a significant minority of these cases has revealed that misinterpretation of the ECG has played a role in as many as 25% of the cases [23] (Figure 4). ST Elevation due to LVH is usually seen in leads V1-V3. Typically, there are QRS amplitude criteria for hypertrophy of the left ventricle and ST segment depressions in the lateral wall leads (V5-V6 and I and aVL). As the amount of LV mass increases, proportionately the ST segment chnges also increase rendering more difficullty in the diagnosis [24]. LVH and bundle branch block represent other frequently encountered patterns in three studies [25-26], which were either misinterpreted or interpreted with disagreement among the interpreters.

Wolff-Parkinson-White is a pre-excitation syndrome, having a accessory pathway leading to characteristic ECG changes of short PR interval, delta waves, wide QRS complexes, and Q wave-T wave vector discordance, with a prevalence rate of about 0.1 to 3.1 per 1000 persons in general population [27]. The pseudo-infarct Q waves resulting from secondary repolarization changes due to altered ventricular activation [28] mimic true infarction, so special attention must be given to make a proper diagnosis. (Figure 5) It is interesting to mention that one of the gentlemen in our study was thrombolyzed twice over a period of 01 year having WPW pattern. Brugada pattern is another pattern mimicking ST elevation associated with a pattern resembling RBBB with elevation of the ST segment in the precordial leads (V1-V2) [29-30]. The Brugada syndrome, though, is linked to an increased risk of ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death secondary to defect in NA channel transport system, but is not an acute cardiac emergency requiring reperfusion therapy. There are mainly three types of Brugada patterns but type I is the most common misinterpreted pseudo-infarct pattern due to a saddle shape ST elevation in V1-V3 but without reciprocal changes (Figure 6). There was a prevalence rate of 2.40% of this pattern in our population presenting in emergency departments getting reperfusion therapy.

The thrombolytic therapy has its own side effects, some of which may be life threatening like intra cranial bleed, major bleeding requiring transfusion, hypersensitivity reactions etc., [31]. Inappropriate fibrinolysis is not without morbidity and mortality [32-34] and any reduction in undue administration of the therapy would be beneficial resulting less complication rates. Also, the thrombolytic therapy also poses a financial burden especially in developing countries like ours where still the emergency services are not completely free yet. There is another way of seeing the thing that if a patient is unduly thrombolyzed, he might be needing in future thrombolysis for a true ischemic event rendering a relative contraindication within next 6 months. So recognition of these patterns is very necessary for accurate supply of thrombolytic therapy for proper management, avoidance of complications and saving cost burden on the patient as well as health system.

For more Lupine Publishers Open

Access Journals Please visit our website:

http://lupinepublishers.us/

For more Research

and Reviews on Healthcare articles Please Click Here:

https://lupinepublishers.com/research-and-reviews-journal/

To Know More About Open Access

Publishers Please Click on Lupine

Publishers

Follow on Linkedin : https://www.linkedin.com/company/lupinepublishers

Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/lupine_online

Thursday, March 25, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| New Materials: Current Developm...

Wednesday, March 24, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| New Materials: Current Developm...

Tuesday, March 23, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| Future Trends in Production and...

Monday, March 22, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Underwater Optical Image Proce...

Saturday, March 20, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | Underwater Optical Image Proce...

Lupine Publishers| Aging, Healthy Families and Narrative Approaches

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Health Research and Reviews

Abstract

Due to the mounting importance of recent research in the areas of healthy families and aging, the paper assesses the particular relationship between old age, health and family life by means of studying the role of grand-parenting and the way it is perceived by older people, the family, and the society at large. The study applies a narrative approach; hence, telling the meaning of the family and grand parenting through personal stories and public discourse, based on the theory of Michel Foucault. The findings put forth suggest that identities of health and family and grand-parenting are built on multiple grounds, and that therefore theory should be sensitized accordingly, as identities are managed at different levels, for different audiences and at different levels of awareness.

Introduction

There has been an interest in aging and family, within sociological developments relating to aging and health policy since the late 1990s (Minkler, 1998). This is a trend that has cut across Canadian, American and European research Cloke et al, 2006; Walker and Naegele [1]; Minkler, 1998; Bengtson et al. [2]; Biggs and Powell [3]; Carmel et al. [4]. The reasons for such expansion are as much economic and political as they are academic. US and European governments recognize that the “family” is important for health and economic needs and this should be reflected in our understanding of aging, family processes and in health policy Beck [5]. “Narrativity” has become established in the health sciences, both as a method of undertaking and interpreting research cf Kenyon et al., 1999; Holstein and Gubrium [6]; Biggs et al. [7] and as a technique for modifying the self McAdams [8]; Mcleod [9]. Both Gubrium [10] and Katz [11] suggest that older people construct their own analytical models of personal identity based on lived experience and on narratives already existing in their everyday environments. By using a narrative approach, the meaning of health and family can be told through stories about the self as well as ones “at large” in public discourse.

Self-storying, draws attention to the ways in which family identities are both more open to negotiation and are more likely to be “taken in” in the sense of being owned and worked on by individuals themselves. Families, of course, are made up of interpersonal relationships within and between generations that are subject to both the formal rhetoric of public discourse, and the self-stories that bind them together in everyday life. The notion of family is, then, an amalgam of policy discourse and everyday negotiation and as such alerts us to the wider health implications of those relationships (cf Powell, 2005). The rhetoric of health policy and the formal representations of adult aging and family life that one finds there, provide a source of raw material for the construction of identity and a series of spaces in which such identities can be legitimately performed. It is perhaps not overstating the case to say that the “success” of a family policy can be judged from the degree to which people live within the stories or narratives of family created by it. In fact, the relationship between healthy families and older people has been consecutively re-written in the health policy literature. Each time a different story has been told and different aspects of the relationship have been thrown into high relief. It might even be argued that the family has become a key site upon which expected norms of intergenerational relations and late-life citizenship are being built. This paper explores the significance of such narratives, using developments in the UK as a case example that may also shed light on wider contemporary issues associated with old age. The structure of the paper is in four constituents. Firstly, we start by mapping out the emergence and consolidation of neoliberal family policy and its relationship to emphasis on family obligation, state surveillance and active citizenship. Secondly, we highlight both the ideological continuities and discontinuities of the subsequent health democratic turn and their effects on older people and the family. Thirdly, research studies are drawn on to highlight how “grand-parenting” has been recognized by governments in recent years, as a particular way of “storying” the relationship between old age and family life. Finally, we explore ramifications for researching family policy and old age by pointing out that narratives of inclusion and exclusion often co-exist. It is suggested that in future, aging and family life will include the need to negotiate multiple policy narratives. At an interpersonal level, sophisticated narrative strategies would be required if a sense of familial continuity and solidarity is to be maintained.

Neoliberalism, Aging, and Healthy Families

Political and health debate since the Reagan/Thatcher years, has been dominated by neoliberalism, which postulates the existence of autonomous, assertive, rational individuals who must be protected and liberated from “big government” and state interference Gray [12]. Indeed, Walker and Naegele [1] claim a startling continuity across Europe is the way “the family” has been positioned by governments as these ideas have spread beyond their original “English speaking” base. Neoliberal policies on health and family, has almost always started from a position of laissez-faire, excepting when extreme behavior threatens its members or wider health relations Beck [5]. Using the UK as a case example, it can be seen that that neoliberal policy came to focus on two main issues. And, whilst both only represent the point at which a minimalist approach from the state touches family life, they come to mark the dominant narrative through which aging and family are made visible in the public domain (Cloke et al. 2006). On the one hand, increasing attention was paid to the role families took in the care of older people who were either mentally or physically infirm. A series of policy initiatives UKG [13-15] recognized that families were a principal source of care and support. “Informal” family care became a key building block of policy toward an aging population. It both increased the salience of traditional family values, independence from government and enabled a reduction in direct support form the state. On the other hand, helping professionals, following US experience Pillemer and Wolf [16], became increasingly aware of the abuse that older people might suffer and the need to protect vulnerable adults from a variety of forms of abuse and neglect Biggs et al. [17]. Policy guidance, “No Longer Afraid: the safe-guard of older people in domestic settings,” was issued in 1993, shortly after the move to seeing informal care as the mainstay of the welfare of older people. As the title suggests, this was also directed primarily at the family.

It is perhaps a paradox that a policy based ostensibly on the premises of leaving-be, combines two narrative streams that result in increased surveillance of the family. This paradox is based largely on these points being the only ones where policy “saw” aging in families, rather than ignoring it. This is not to say that real issues of abuse and neglect fail to exist, even though UK politicians have often responded to them as if they were some form of natural disaster unrelated to the wider policy environment. To understand the linking of these narratives, it is important to examine trends tacit in the debate on family and aging, but central to wider health policy. Wider economic priorities, to “roll back the state” and thereby release re-sources for individualism and free enterprise, had become translated into a family discourse about caring obligations for ill relatives and the need to enforce them. If families ceased to care, then the state would have to pick up the bill. Families, rather than being seen as “havens against a harsh world,” were now easily perceived as potential sites of mistreatment, and the previously idealized role of the unpaid carer became that of a potential recalcitrant, attempting to avoid their family obligations. An attempt to protect a minority of abused elders thus took the shape of a tacit threat, hanging above the head of every aging family Biggs and Powell [18]. It is worth note that these policy developments took little account of research evidence indicating that family solidarity and a willingness to care had decreased in neither the UK Wenger, 1994; Phillipson [19] nor the US Bengtson and Achenbaum [20]. Further, it appeared that familial caring was actually moving away from relationships based on obligation and toward ones based on negotiation Finch and Mason [21]. Family commitment has, for example, to vary depending upon the characteristic care-giving patterns within particular families. Individualistic families provided less instrumental help and made use of welfare services, whereas a second, collectivist pattern offered greater personal support. Whilst this study focused primarily on upward generational support, Silverstein and Bengtson [22] observed that “tight-knit” and “detached” family styles were often common across generations. Unfortunately, policy developments have rarely taken differences in care-giving styles into account, preferring a general narrative of often idealized role relation-ships. It is not unfair to say that during the neoliberal period, the dominant narrative of family became that of a site of care going wrong.

Health Democracy, Aging, and the Family

Health democratic policies toward the family arose from the premise that by the early 1990s, the free-market policies of the Thatcher/Reagan years had seriously damaged the health fabric of the nation state and that its citizens needed to be encouraged to identify again with the national project. A turn to an alternative, sometimes called “the third way,” emerging under Clinton, Blair and Schroeder administrations in the US and parts of Europe, attempted to find means of mending that health fabric, and as part of it, relations between older people and their families Beck [5]. The direction that the new policy narrative took is summarized in UK Prime Minister Blair’s [23] statement that “the most meaningful stake anyone can have in society is the ability to earn a living and support a family.” Work, or failing that, work-like activities, plus an active contribution to family life began slowly to emerge, delineating new narratives within which to grow old Hardill et al. [24]. Giddens [25] in the UK and Beck [26] in Germany, both proponents of health democratic politics, have claimed that citizens are faced with the task of piloting themselves and their families through a changing world in which globalization has transformed our relations with each other, now based on avoiding risk. According to Giddens [25], a new partnership is needed between government and civil society. Government support to the renewal of community through local initiative, would gives an increasing role to “voluntary” organizations, encourages health entrepreneurship and significantly, supports the “democratic” family characterized by “equality, mutual respect, autonomy, decision-making through communication and freedom of violence.” It is argued that health policy should be less concerned with “equality” and more with “inclusion,” with community participation reducing the moral and financial hazard of dependence cf Walker, 2002; Biggs et al. [7]; Powell and Owen [27]; Walker and Aspalter [28].

Through an increased awareness of the notion of ageism, the influence of European ideas about health inclusion and North American health communitarianism, families and older people found themselves transformed into active citizens who should be encouraged to participate in society, rather than be seen as a potential burden upon it Biggs [29]. A contemporary UK policy document, entitled “Building a Better Britain for Older People” DSS [30] is typical of a new genre of western policy, re-storying the role of older adults: “The contribution of older people is vital, both to families, and to voluntary organisations and charities. We believe their roles as mentors-providing ongoing support and advice to families, young people and other older people-should be recognised. Older people already show a considerable commitment to volunteering. The Government is working with voluntary groups and those representing older people to see how we can increase the quality and quantity of opportunities for older people who want to volunteer.” What is perhaps striking about this piece is that it is one of the few places where families are mentioned in an overview on older people, with the exception of a single mention of carers, many of whom, it is pointed out, “are pensioners themselves.” In both cases the identified role for older people constitutes a reversal of the narrative offered in preceding policy initiatives. The older person like other members of family structure is portrayed as an active member of the health milieu, offering care and support to others Hardill et al. [24].

The dominant preoccupation of this policy initiative, is not however, concerned with families. Rather, there is a change of emphasis toward the notion of aging as an issue of lifestyle, and as such draws on contemporary gerontological observations of the “blurring” of age-based identities (Featherstone and Hepworth, 1995) and the growth of the grey consumer Katz [11]. Whilst such a narrative is attractive to pressure groups, voluntary agencies and, indeed, health gerontologists; there is, just as with the policies of the neoliberals, an underlying economic motive which may or may not be to the long term advantage to older people and their families. Again, as policies develop, the force driving the story of elders as active citizens was to be found in policies of a fiscal nature. The most likely place to discover how the new story of aging, fits the bigger picture is in government-wide policy. In this case the document has been entitled “Winning the Generation Game” UKG [31]. This begins well with “One of the most important tasks for twentyfirst century Britain is to unlock the talents and potential of all its citizens. Everyone has a valuable contribution to make, throughout their lives.” However, the reasoning behind this statement becomes clearer when policy is explained in terms of a changing demographic profile: “With present employment rates” it is argued, “one million more over-50s would not be working by 2020 because of growth in the older population. There will be 2 million fewer working-age people under 50 and 2 million more over 50: a shift equivalent to nearly 10 percent of the total working population.”

The solution, then, is to engage older people not only part of family life but also in work, volunteering or mentoring. Older workers become a reserve labor pool, filling the spaces left by falling numbers of younger workers. They thus contribute to the economy as producers as well as consumers and make fewer demands on pensions and other forms of support. Those older people who are not thereby healthly included, can engage in the work-like activity of volunteering. Most of these policy narratives only indirectly affect the aging family. Families only have a peripheral part to play in the story, and do not appear to be central to the lives of older people. However, it is possible to detect the same logic at work when attention shifts from the public to the private sphere. Here the narrative stream develops the notion of “grand-parenting” as a means of health inclusion. This trend can be found in the UK, in France Girard and Ogg [32], Germany Scharf and Wenger [33], as well as in the USA Minkler [34]. In the UK context the most detailed reference to grand-parenting can be found in an otherwise rather peculiar place-namely from the Home Offic-an arm of British Government primarily concerned with law and order. In a document entitled “Supporting Families” (2000b), “family life” we are told, “is the foundation on which our communities, our society and our country are built.” “Business people, people from the community, students and grandparents” are encouraged to join a schools mentoring network. Further, “the interests of grandparents, and the contribution they make, can be marginalized by service providers who, quite naturally, concentrate on dealing with parents. We want to change all this and encourage grandparents-and other relativesto play a positive role in their families.” By which it is meant: “home, school links or as a source of health and cultural history” and support when “nuclear families are under stress.” Even older people who are not themselves grandparents can join projects “in which volunteers act as “grandparents” to contribute their experience to a local family.” In the narratives of health democracy, the aging family is seen as a reservoir of potential health inclusion. Older people are portrayed as holding a key role in the stability of both the public sphere, through work and volunteering, and in the private sphere, primarily through grandparental support and advice (Cloke et al. 2006). Grandparents, in particular, are storied as mentors and counselors across the public and private spheres. Whilst the grandparental title has been used as a catch-all within the dominant policy narrative; bringing with it associations of security, stability and an in many ways an easier form of relationship than direct parenting; it exists as much in public as in private space. It is impossible to interpret this construction of grandparenthood without placing it in the broader project of health inclusion, itself a response to increased health fragmentation and economic competition. Indeed it may not be an exaggeration to refer this construal of grand-parenting as neofamilial. In other words, the grandparent has out-grown the family as part of a policy search to include older adults in wider society. The grandparent becomes a mentor to both parental and grandparental generations as advice is not restricted to schools and support in times of stress, but also through participation in the planning of amenities and public services BGOP [35]. This is a very different narrative of older people and their relationship to families, from that of the dependent and burdensome elder. In the land of policy conjuring, previously conceived problems of growing economic expense and health uselessness have been miraculously reversed. Older people are now positioned as the solution to problems of demographic change, rather than their cause. They are a source of guidance to ailing families, rather than their victims. Both narratives increase the health inclusion of a potentially marginal health group: formerly known as the elderly.

“Grand-Parenting” Policy

There is much to be welcomed in this story of the active citizen elder. Especially so if policy-inspired discourse and lived self-narratives are taken to be one and the same. There are also certain problems, however, if the two are unzipped, particularly when the former is viewed through the lens of what we know about families from other sources. First, each of the roles identified in the policy domain, volunteering, mentor-ship and grand-parenting, have a rather second–hand quality. By this is meant that each is supportive to another player who is central to the task at hand. Rather like within Erikson’s psycho-health model of the lifecycle, the role allocated to older people approximates grand-generativity and thereby contingent upon the earlier, but core life task of generativity itself Kivnick [36]. In other words it is contingent upon an earlier part of life and the narratives woven around it, and fails to distinguish an authentic element of the experience of aging. When the roles are examined in this light, a tacit secondary status begins to emerge. Volunteering becomes unpaid work; mentoring, support to helping professionals in their eroded pastoral capacities; and grand-parenting, in its familial guise, a sort of peripheral parent without the hassle. This peripherality may be in many ways desirable, so long as there is an alternative pole of authentic attraction that ties the older adult into the health milieux. Either that or the narrative should allow space for legitimized withdrawal from healthy inclusive activities. Unfortunately, the dominant policy narrative has little to say on either count. Second, there is a shift of attention away from the most frail and oldest old, to a third age of active or positive aging, which, incidentally, may or may not take place in families. It is striking that a majority of policy documents of what might be called the “new aging,” start counting from age 50, an observation that is true for formal government rhetoric and pressure from agencies and initiatives lead by elders Biggs [37]. This interpretation of the life-course has been justified in terms of its potential for forming intergenerational alliances BGOP [35] and fits well with the economic priority of drawing on older people as a reserve labor force UKG [38].

Third, there is a striking absence of analysis of family relations at that age. Possibilities of intergenerational conflict as described in other literature De Beauvoir [39], not least in research into threegeneration family therapy Hargrave and Anderson [40]; Qualls [41] plus the everyday need for tact in negotiating childcare roles Bornat et al. [42]; Waldrop et al. [43], appear not to have been taken into account. This period in the aging life-course is often marked by midlife tension and multi-generational transitions, such as those experienced by late adolescent children and by an increasingly frail top generation Ryff and Seltzer [44]. Research has indicated that solidarity between family generations is not uniform and will involve a variety of types and degrees of intimacy and reciprocity Silverstein and Bengtson [22]. Finally, little consideration has been given to the potential conflict between the tacit hedonism of aging lifestyles based on consumption and those more healthly inclusive roles of productive contribution, of which the “new grandparenting” has become an important part. Whilst there are few figures on grandparental activity it does, for example, appear that community volunteering amongst older people is embraced with much less enthusiasm than policy-makers would wish Boaz et al. [45]. Chambre [46] claims volunteering in the US diminishes in old age. Her findings indicate the highest rates of volunteering occur in mid-life, where nearly two thirds volunteer. This rate declines to 47 percent for persons aged between 65 and 74 and to 32 percent among persons 75 and over. A UK Guardian-ICM (2000) poll of older adults indicated that, amongst grandfathers, but not grandmothers, there was a degree of suspicion of child-care to support their own children’s family arrangements. More than a quarter of men expressed this concern, compared with only 19 percent of women interviewed. The UK charity, Age Concern, stated: “One in ten grandparents are under the age of 56. They have 10 more years of work and are still leading full lives.”

One might speculate, immersed in this narrative stream, that problematic family roles and relationships cease to exist for the work-returning, volunteering and community enhancing 50-plus “elder.” Indeed, the major protagonists of health democracy seem blissfully unaware of several decades of research, particularly feminist research, demonstrating the mythical status of the “happy family” cf e.g. Land [47]. What emerges from research literature on grand-parenting as it is included in people’s everyday experience and narratives of self, indicates two trends: (1) there appears to be a general acceptance of the positive value of relatively loose and undemanding exchange between first and third generations, and (2) that deep commitments become active largely in situations of extreme family stress or breakdown of the middle generation. First, grandparents have potential to influence and develop children through the transmission of values. Subsequently, grand-parents serve as arbiters of knowledge and transmit knowledge that is unique to their identity, life experience and history. In addition, grandparents can become mentors, performing the function of a generic life guide for younger children. This “transmission” role is confirmed by Mills [48] study of mixed gender relations and by Waldrop et al. [43] report on grandfathering. According to Roberto [49] early research on grand-parenting in the USA has attempted to identify the roles played by grandparents within the family system and towards grandchildren. Indeed, much US work on grandparenting has focused on how older adults view and structure their relationships with younger people. African American grandparents, for example, take a more active role, correcting the behavior of grandchildren and acting like “protectors” of the family. Accordingly, such behaviors are related to effects of divorce and under/ unemployment. Research by Kennedy [50] indicates, however, that there is a cultural void when it comes to grand-parenting roles for many white families with few guide-lines on how they should act as grandparents. Girard and Ogg [32] report that grand-parenting is a rising political issue in French family policy. They note that most grandmothers welcome the new role they have in child care of their grandchildren, but there is a threshold beyond which support interferes with their other commitments. Contact between older parents and their grandchildren is less frequent that with youngsters, with financial support becoming more prominent.

Two reports, explicitly commissioned to inform UK policy Hayden et al. [51]; Boaz et al. [45] classify grand-parenting under the general rubric of intergenerational relationships. Research evidence is cited, that “when thinking about the future, older people looked forward to their role as grandparents” and that grandparents looked after their grandchildren and provided them with “love, support and a listening ear,” providing childcare support to their busy children and were enthusiastic about these roles. Hayden et al. [51] used focus groups and qualitative interviewing and report that: “grand-parenting included spending time with grandchildren both in active and sedentary hobbies and pursuits, with many participants commenting on the mental and physical stimulation they gained from sharing activities with the younger generation. Coupled with this, the Beth Johnson Foundation (1998) found that older people as mentors had increased levels of participation with more friends and engendered more health activity. With the exception of the last study, each has relied on exclusive self-report data, or views on what grand-parenting might be like at some future point. In research from the tradition of examining health networks, and thus not overtly concerned with the centrality of grand-parenting or grandparent-like roles as such, it is rarely identified as a key relationship and could not be called a strong theme. Studies on the UK, Phillipson et al. [52], Japan Izuhara [53], the US Schreck [54]; Minkler [34], Hispanic Americans Freidenberg [55], and Germany, Chamberlayne and King [56] provide little evidence that grand-children, as distinct from adult children, are prominent members of older peoples reported health networks. Grandparental responsibility becomes more visible if the middle generation is for some reason absent. Thompson [57] reports from the UK, that when parents part or die, it is often grandparents who take up supporting, caring and mediating roles on behalf of their grandchildren. The degree of involvement was contingent however on the quality of emotional closeness and communication within the family group. Minkler [34] has indicated that in the US, one in ten grandparents has primary responsibility for raising a grandchild at some point, with care often lasting for several years.

This trend varies between ethnic groups, with 4.1 percent White, 6.55 percent Hispanic and 13.55 African American children living with their grandparents or other relatives. It is argued that a 44 percent increase in such responsibilities is connected to the devastating effects of wider health issues, including AIDS/HIV, drug abuse, parental homelessness and prison policy. Thomson and Minkler [58] note that there is an increasing divergency in the meaning of grand-parenting between different socio-economic groups, with extensive care-givers (7 percent of the sampled population) having increasingly fewer characteristics in common with the 14.9 percent who did not provide child-care. In the UK, a similar split has been identified with 1 percent of British grandparents becoming extensive caregivers, against a background pattern of occasional or minimal direct care Duckworth [59]. It would appear that grand-parenting is not, then a uniform phenomenon, and extensive grand-parenting or grandparent-like activities are rarely an integral part of health inclusion. Rather, whilst it is seen as providing some intergenerational benefit, it may be a phenomenon that requires an element of un-intrusiveness and negotiation in its non-extensive form. When extensively relied on it is more likely to be a response to severely eroded inclusive environments and the self-protective reactions of families living with them. Minkler’s analysis draws attention to race as a feature of health exclusion that is poorly handled by policy narratives afforded to the family and old age. There is a failure to recognize structural forms of inequality, and action seeking to healthly include older people as a category appears to draw heavily on the occasional helper and health volunteer as a dominant narrative.

Each phase of health policy, be it the Reagan/Thatcherite neoliberalism of the 1980s and early 1990s, the Clinton/Blairite interpretation of health democracy in the late 90s, or the millennial Bush administration, leaves a legacy. Moreover, policy development is uneven and subject to local emphasis and elision, which means that it is quite possible for different, even conflicting narratives of family and later life to coexist in different parts of the policy system. Each period generates a discourse that can legitimate the lives of older people and family relations in particular ways, and as their influence accrues, create the potential of entering into multiple narrative streams. A striking feature of recent policy history has been that not only have the formal policies been quite different in their tenor and tacit objectives, one from another, they have also addressed different areas of the lives of aging families. Where there is little narrative overlap there is the possibility of both policies existing, however opposed they may be ideologically or in terms of practical outcome. Different narratives may colonize different parts of policy, drawing on bureaucratic inertia, political inattention and convenience to maintain their influence. They have a living presence, not least when they impinge on personal aging.b Also, both policy discourses share a deep coherence, which may help to explain their co-existence. Each offers a partial view of aging and family life whilst downloading risk and responsibility onto aging families and aging identities. Neither recognizes aging which is not secondary to an independent policy objective. Both mask the possibility of authentic tasks of aging. If the analysis outlined above is accepted, then it is possible to see contemporary health policy addressing diverse aspects of the family life of older people in differing and contradictory ways. Contradictory narratives for the aging family exist in a landscape that is a one and the same time increasingly blurred in terms of roles and relationships and splitoff in terms of narrative coherence and consequences for identity. Indeed in a future of complex and multiple policy agendas, it would appear that a narrative of health inclusion through active aging can coexist with one emphasizing carer obligation and surveillance. Such a co-existence may occasionally become inconvenient at the level of public rhetoric. However, at an experiential and ontological level, that is to say at the level of the daily lives of older adults and their families, the implications may become particularly acute. Multiple co-existing policy narratives may become a significant source of risk to identity maintenance within the aging family.

One has to imagine a situation in which later lives are lived, skating on a surface of legitimizing discourse. For everyday intents and purposes this surface supplies the ground on which one can build an aging identity, relate to other family members and immediate community. However, there is always the possibility of slipping, of being subject to trauma or transition. Serious slippage will provoke being thrown onto a terrain that had previously been hidden, an alternative narrative of aging with entirely different premises, relationship expectations and possibilities for personal expression. Policy narratives, however, are also continually breaking down and fail to achieve hegemony as they encounter lived experience. Indeed, it could be argued that a continuous process of re-constitution takes place via the play of competing narratives. When we are addressing the issue of older people’s identity in later life we can usefully note Foucault’s [60] contention that there has been a growth in attempts to control national populations through discourses of normality, but at the same time this has entailed increasing possibilities for self-government. Part of the attractiveness of thinking in terms of narrative, that policies tell us stories that we don’t have necessarily to believe, is the opening of a critical distance between description and intention. Policy narratives describe certain, often idealized, states of affairs. Depicting them as stories, rather than realities, allows the interrogation of the space between that description and experience (cf Powell, 2005).

Conclusion

What does this examination of health policy discourse and everyday stories of family and aging selves tell us, and what are the lessons for future health research? Firstly, we are alerted to the partial nature of the narratives supplied by health policy, which affects our perception of families as well as of older people. The simplifying role of policy discourse tends to highlight certain, politically valued, aspects of experience to the exclusion of other possibilities [61-63]. These are also the discourses most likely to be reflected in health policy-sponsored research. Secondly, the inclusion of certain roles, activities and age bands in policy discourse has a legitimizing role. In other words, it not only sanctions the direction of resources and the action of helping professionals important though that is. It also contributes to the legitimated identities afforded to people in later life. This includes at least two factors key to aging identity: the creation of health spaces in which to perform aging roles and be recognized as such, and, the supply of material with which explicit yet personal narratives of self and family can be made [64-66]. Thirdly, a significant element in the “riskiness” of building aging and healthy family identities under contemporary conditions may arise from the existence of multiple policy discourses that personal narratives, of family, self and relations between the two, have to negotiate [67,68]. Research on the management of identity, should, then, be sensitized to the multiple grounds on which identity might be built and the potential sources of conflict and uncertainty may bring. Fourthly, attention should be paid to the relationship between tacit and explicit influences on identity management in late-life families. The multiple sources for building stories “to live by” and the tension between legitimizing discourses and alternative narratives of self and family, would suggest that identities are managed at different levels, for different audiences and at different levels of awareness [69,70]. There are implications here for both the conceptualization of familial and policy relations and for the practice of research. The story that the researcher hears and then records may be tapping a particular level of disclosure.

For more Lupine Publishers Open

Access Journals Please visit our website:

http://lupinepublishers.us/

For more Research

and Reviews on Healthcare articles Please Click Here:

https://lupinepublishers.com/research-and-reviews-journal/

To Know More About Open Access

Publishers Please Click on Lupine

Publishers

Follow on Linkedin : https://www.linkedin.com/company/lupinepublishers

Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/lupine_online

Friday, March 19, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers | The Dynamics of Mounds-Cluster...

Wednesday, March 17, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| Parental Perspective Pre- and P...

Monday, March 15, 2021

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| How Might the UK Government Eng...

Friday, March 12, 2021

Lupine Publishers| Features of the Functional State of Patients with the Closed Breaks of Shoulder and Shin at Treatment on Ilizarov

Abstract

The Federal State Financed Institution Russian Ilizarov Scientific Center for Restorative Traumatology and Orthopaedics. A comparative survey of stiffness fixation of bone fragments and blood supply to regenerate in two groups of adult patients with closed fractures of the shoulder (35 pers.) and fractures of the tibia (35 pers.) in terms of treatment by Ilizarov. Found that when a shoulder injury significantly lower functional load carried by the limb and 3 times higher than recorded by a load cell micromotion bone fragments when dosed loading segment of the limb. At the turn of the humerus faster and increases blood flow in normal vessels regenerate bone.

Keywords: Fractures of the humerus; Tibia fracture; Transosseous osteosynthesis; The blood supply to regenerate bone

Introduction

On the basis of information about the regeneration of the broken bones of front and back extremities experimental zoons a priori had opinion of absence of principle differences in the regeneration of the broken bones of overhead and lower extremities for people. Ilizarov at treatment of patients with the closed breaks of both humeral bone and bones of shin recommended to adhere to the identical optimum terms of fixing 54 days [1]. Not taken into account thus, that lower extremities, unlike overhead. The feature of the functional state of patients at treatment of break of humeral bone is falling of capacity at the maintainance of lokomotornoy activity. The closeness of proksimal’noy part of shoulder to the corps and necessity of maintainance of motions in an elbow joint do impossible using for treatment of break of humeral bone of typical set of circular supports of vehicle of Ilizarova, in-use at treatment of sick with breaks bones of shin [2]. For the union of breaks of bones a large value is had feature of their providing with blood, more intensive on a shoulder [3-5]. The purpose of the real research was comparison of capacity for the static functional ladening of shoulder and shin, and also inflexibility of fixing of bone fragments and providing with blood of regeneratе at treatment on Ilizarov of the closed diafizarnykh breaks of bones of these segments of extremities.

A Volume and Research Methods

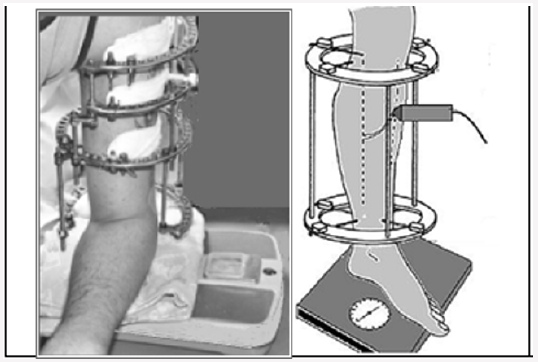

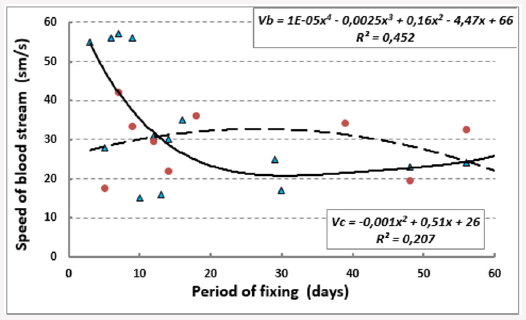

Inspected 2 groups of patients. First made 35 patients with the closed diafiz breaks of humeral bone in the conditions of treatment on the method of Ilizarov. Age of patients from 26 to 66 years (40±3), women - 10 brows., term of fixing in the moment of inspection from 3 to 94 days (22±6). The second group was made by 35 patients of mature age with the closed diafiz breaks of bones of shin in the conditions of treatment on the method of Ilizarov. For all patients micromobility оf fragments of humeral or shinbones was determined at the axial ladening of the proper extremity dosed, step increasing for 5kG [6]. Thus by tenzometric statio and voltmeter of B7-73/1 a signal, allowing at a count to define the change of distance between spokes, going out from a bone higher and below than area of break, was registered. In addition, by a sensor with bearing frequency 8 Mhz of computer-controlled diagnostic complex «Angiodin-2UK production amalgamation of «BIOSS» (Russia) speed of blood stream was registered in the area of break on the surface of tibia or on the outward surface of humeral bone at the step increasing functional ladening of shin or shoulder (Figure 1). Statistical treatment of results of researches was conducted by the package of analysis of data of Microsoft ExSel-2010 [7]. For the estimation of authenticity of distinctions of results used the t-criterion of St’yudent. Applied the methods of cross-correlation and regressive analysis.

Figure 1: Axial functional ladening of shoulder and shin in the period of treatment of patients on Ilizarov with determination of change of distance between spokes and registration of speed of blood stream.

Research Results

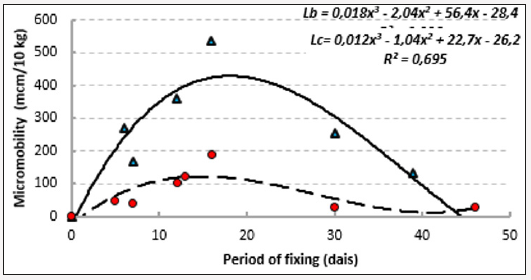

Figure 2: Dynamics of mikromobility of bone fragments at treatment of patients with the breaks of humeral and tibia bone.

The Most substantial differences in the indexes of two groups of patients are exposed at the estimation of the functional loading on extremity. If able to carry most sick with a break bones of shin on the damaged extremity mass of body, for patients with the break of shoulder the maximal loading was 15,9±1,3 kG and accompanied appearance of the pain feelings. Micromotion of bone fragments in the period of fixing for the patients of 1th and 2th groups changed identically, increasing in the first two weeks after osteosintezis because of rezorbtion of ends of fragments. At the breaks of shoulder in the first 2 weeks it made 219±39 mkm/10kG., at the breaks of tibia of 71±18mkm/10kG. In a subsequent period of treatment mikropomotions of bone fragments in both groups steadily went down because of kompaktizations of bone regeneratе (Figure 2). To one of reasons of distinctions in reologic properties of bone regeneratе for patients at the beginning of period of fixing there could be features of construction of vehicle of Ilizarov at treatment of traumas of shoulder (not rings, but semi-supports, are used in overhead and lower third of shoulder). Nevertheless, so substantial distinctions in indexes allow to assert that properties of bone regeneratе of shoulder differ from properties of regeneratе of tibia. Certain differences are exposed and in the indexes of speed of blood stream in vessels bone regenerate of shoulder and shin. Speed of blood stream in regenerate of shoulder was evened 32,4 ±3,4сm/s, and shins –26,6 ±3,2сm/s.

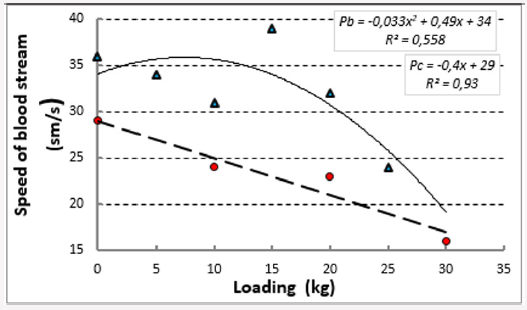

Speed of blood stream in the vessels of shoulder was most in the first days after a trauma and went down during the first month of period of fixing (Figure 3). Speed of blood stream in the vessels of shin was increased during the first week of treatment and went down during the period of fixing. Speed of blood flow of bone regeneratе largely depended on inflexibility of fixing of bone fragments. As far as the increase of mikromobility of fragments to 180mkm/10kG speed of blood stream was increased as for the patients of 1th group so for patients with the breaks of bones of shin. There were less values of intensity of local blood stream at the large sizes of mikromobility. During the leadthrough of test with an increasing axleloading on a shoulder speed of blood stream in arteries began to go down. Under reaching loading of 15kG there was a temporal increase of index, related to the decline of intramural pressure in the wall of arteries and diminishing of vascular resistance (Figure 4).

Figure 3: A dynamics of speed of blood stream is in the vessels of bone regenerats of shoulder and tibia.

Figure 4: A dynamics of speed of blood stream is in the vessels of bone regenerats of shoulder and tibia.

The further increase of pressure resulted in the rapid decline of speed of blood stream because of the mechanical ceiling of vascular river-bed and appearance of the pain feelings. The same dynamics of change speed of blood stream was observed and at the increase of loading on a shin. It is known that for the vessels of shin in a pose upright characteristically more high blood pressure (action of additional hydrostatical pressure the size of which exceeds 70mm of rt.st.). During the leadthrough of research in a pose upright patients with the increase of the functional loading on extremity had a decline of speed. On a background the steady decline of speed of blood stream under reaching loading of 20kG the relative increase of index is exposed. It allows to draw conclusion that the vessels of bone regeneratе of shin are better protected from the action of loading enclosed from outside. This defence is determined more high values of hydrostatical pressure and, presumably, by the morphological features of bone regeneratе. Thus, the existent difference of functional destiny of overhead and lower extremities for people lays on the imprint on their state in the period of treatment of breaks of bones. Even in the conditions of application of method of Ilizarov there is ability to carry the functional loading at a shoulder less than in 2-3 times below, than at a shin. In the period of treatment of humeral bone considerably anymore pliability of bone regeneratе during the leadthrough of test with the functional loading. Speed of blood stream after the break of shoulder.

For more Lupine Publishers Open

Access Journals Please visit our website:

http://lupinepublishers.us/

For more Research

and Reviews on Healthcare articles Please Click Here:

https://lupinepublishers.com/research-and-reviews-journal/

To Know More About Open Access

Publishers Please Click on Lupine

Publishers

Follow on Linkedin : https://www.linkedin.com/company/lupinepublishers

Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/lupine_online

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| A Standard Pediatric Dental Clinic

Lupine Publishers: Lupine Publishers| A Standard Pediatric Dental Clinic : Lupine Publishers| Journal of Dentistry and Oral Health Care Aft...

-

Lupine Publishers | Journal of Health Research and Reviews Abstract Metabolism is the process your body uses to make energy f...

-

Heat wave killings in Pakistan and possiblestrategies to prevent the future heat wave fatalities by Syed Zawar Shah in Research and ...

-

To Examine the Relationship and Strength of Alcohol-Related Intimate Partner Violence in sub-Saharan Africa by Ekpenyong MS in Rese...