Lupine Publishers | Journal of Health Research and Reviews

Abstract

This research examined the preponderance of culture noise as barrier

in the channel of communication between health care

providers and patients. The primary objective of the study was to assess

how cultural health beliefs influenced the effectiveness

of communication between health care providers and patients at the Ogume

Primary Health Care Centre in Ndokwa West Local

Government Area of Delta State. A total of 134 respondents were

purposively selected and studied in this work. The triangulation

approach was adopted, using a combination of both survey and in depth

interview methods. While the survey method used the

instrument of questionnaire for data collection, the in depth interview

used the interview guide. The theory of Reasoned Action

provided the framework for the study. The results of the study showed

that the contrariness in the cultural health beliefs of health

care providers and patients negatively influenced the communication

between both parties. Hence, majority of the respondents

exhibited healthcare-default-behaviours such as non-adherence to

doctor’s prescriptions, self-medication and outright resort to

traditional medicine therapy. Therefore, the paper recommends, among

others, adequate education of health care providers to

make them knowledgeable about these cultural health beliefs in rural

settings and their significance in achieving effective provider-

Patient communication as a precursor to securing patients’ confidence,

dependence and adherence to medical instructions.

Introduction

This study was inspired by two separate health related incidents

the researcher was recently exposed to. One was fatal and the other,

which would have been as tragic, was reversed because of timely

intervention by medical orthodoxy. The first was the regrettable

death of a 40years old, educated mother who died during childbirth

at the home of a traditional medicine woman despite medical advice

that the baby in her womb was lying bridged. The second was the

near blindness of my mother from cataract despite being diagnosed

of the problem many years ago by orthodox medical science. While

my mother managed her sight problem with dew drops collected

from cocoyam leaves culturally believed to be efficacious for such

state; the deceased believed the traditional medicine woman

possessed the spiritual powers to ward off the malevolent forces

purportedly responsible for the bridged state of her pregnancy.

Both cases point to the problem of how cultural health beliefs could

constitute noise in the channel of communication between health

care providers and patients. Perhaps if the message of what needed

to be done was effectively communicated in the two cases cited

above, the deceased mother would still be alive and my mother

would have received timely surgical intervention to correct her sight

problem long before now! Health communication is the study and

practice of communicating promotional health information, such as

in public health campaigns, health education, and between doctor

and patients Abroms & Maibach [1]. One of the major purposes of

health communication is to inculcate health literacy in patients that

will enable them make informed personal health choices. It has

been proposed that strong, clear and positive relationships with

physicians can radically improve and increase the condition of a patient

Noar et al. [2]. This is why Edgar and Hyde [3] recommend

interpersonal communication between health care providers

and patients as one of the most effective strategies for achieving

positive health outcomes in patients. Frank et al. [4] corroborate

this position by affirming that effective communication between

physicians and their patients has been associated with patient

outcomes which, incidentally, is the ultimate goal of the health

care providers/patient communication Fong, Anat and Longnecker

[5]. Unfortunately, studies have shown that the goal of achieving

effective communication between health care providers and their

patients has always been beset by a number of barriers one of

which is patients’ cultural beliefs Diette & Rand [6]; Tongue et al.

[7] Recent consensus in public health and health communication

reflects increasing recognition of the important role of culture

as a factor associated with health and health behaviours, as well

as a potential means of enhancing the effectiveness of health

communication programmes and interventions Institute of

Medicine, in kreuter and Mc Clure [8].

Africa, in the portrayal of Andrews and Boyles, in Singleton,

Elizbeth & Krause [9] belongs to the magico-religious and

deterministic groups. While the magico-religious group believes in

supernatural forces or evil spirits inflicting people with ailments as

punishment for sin or the handiwork of evil ones who cast spells

on people; the determinist group believes in the preordainment of

ailments and cure. A corollary to this belief system is the extended

belief in the power of traditional medicine men and the efficacy of

their charms and herbs to reverse the ill-fortune of ill-health. This

predisposition and predilection towards cultural health beliefs and

traditional medicine as an alternative to orthodox medicine has

always constituted a noise element in the effective communication

between health care providers and patients in Africa. This feeling

is expressed in defaults in medical care such as non-adherence

to medical instructions, self medication, procrastinated resort

to medical advice and their attendant complications for health

outcomes. Interestingly, despite the gloomy scenario painted above,

Ojua [10] and Kakung [11], equal believers in the above position, now

express the sentiment that development, civilization and education,

among other factors, have helped to introduce tremendous change

in the beliefs and bahaviour of Africans to orthodox medicine

patronage. Is this true? To be certain, it has become imperative that

a study be conducted to establish the influence of cultural beliefs

on the communication between healthcare providers and the rural

dwellers; their compliance with healthcare providers prescriptions;

and the health information seeking behaviour they exhibit.

Statement of Problem

One of the major purposes of health communication is to

inculcate health literacy in patients that will enable them make

informed personal health choices and decisions. To achieve

this purpose, Edgar and Hyde [3] recommend interpersonal

communication between health care providers and patients as

one of the most effective strategies for achieving positive health

outcomes in patients, which incidentally, is the ultimate goal of

the health care providers and patient communication Fong, Anat

and Longnecker [5]. After all, patients are the raison’ deter for the

establishment of hospitals, the training of medical personnel and

all the extensive medical programmes of governments all over the

world. Recent consensus in public health and health communication

reflects increasing recognition of the important role of culture as

a factor associated with health and health behaviours (institute of

medicine, in Kreuter and Mc Clure [8]. Africa, in the portrayal of

Andrews and Boyle, in Singleton Elizabeth and Krause [9], belongs

to the magico-religious and determinist cultural belief groups,

who believe that health problems are caused by factors such as

supernatural forces, evil forces, enchantment, preordainment, etc

and that cure can only come from the intervention of powerful

medicine men making use of their charms and herbs. This cultural

belief system is usually expressed in defaults in orthodox medical

care such as resort to alternative medicine, non-adherence to

medical advice and prescriptions, self medication, procrastinated

resort to medical advice and their attendant consequences for

health outcomes such as deterioration of patient health condition,

worsening disease, treatment failures, increased hospitalization,

deaths and increased health care costs Osterberg and Blaschke [12].

In Nigeria, right down to the grassroots, the problem of ill-health

is further compounded by our collectivistic cultural orientation

under which every sick person requires at least one, or more,

healthy family member(s) to take care of him. The cumulative loss of

man hours arising from this situation has far-reaching implications

for our productive capacity as a people. while some studies show

that the goal of achieving effective communication between health

care providers and patients for better health outcomes are still

beset by a number of problems one of which is patients cultural

beliefs Diette & Rand [6]; Tongue et al. [7] others indicate that

development, civilization and education have helped to introduce

tremendous change in the beliefs and behaviour of Africans in this

regard Ojua [10]; Kakung [11], thereby creating a knowledge gap.

Therefore, this study is necessitated by a need to fully comprehend

the place of cultural beliefs in achieving effective interpersonal

communication between health care providers and patients as

a precursor to securing patients’ confidence, dependence and

adherence to orthodox medication.

Objectives of The Study

a) The objectives of the study are as follows:

b) To establish whether cultural health beliefs influence the

interpersonal communication between health care providers

and patients at the Ogume primary health care centre.

c) To determine the extent of influence of cultural beliefs

on the patients’ adherence to medical recommendations and

prescriptions at the centre.

d) To ascertain the influence of cultural health beliefs on the

patients’ health seeking behaviour.

Research Questions

RQ. 1: Do the cultural health beliefs of patients at Ogume

primary health care centre influence their communication with

health care providers?.

RQ. 2: To what extent are the patients’ adherence to health care

providers prescriptions at the centre influenced by their cultural

health beliefs?.

RQ. 3: How do the cultural health beliefs of the patients at the

health centre influence their health seeking behaviour?.

Operational Definition of Terms

Culture: The beliefs of the respondents regarding traditional

medicine practice based on the diagnostic and therapeutic power

of supernatural forces, herbs, stems, roots and other ingredients

associated with the practice.

Health Beliefs: The beliefs of the respondents on the diagnostic

and therapeutic efficacy of traditional medicine.

Healthcare Providers: The Ogume primary healthcare center

staff comprising the doctor, midwives, nurses, health assistants

and record keepers who render healthcare services to patients in

Ogume community who patronize the Ogume primary health care

center.

Culture Noise: The cultural health beliefs of the respondents

that make it psychologically difficult for them to listen, understand,

strictly adhere and implement to the letter the medical instructions,

prescriptions, recommendations and advice communicated to

them by the health care providers in the Ogume Primary Health

Care Center.

Barrier: That which obstructs the reception, comprehension and

adoption of health messages communicated between the healthcare

providers and patients of Ogume primary healthcare center.

Healthcare Provider/Patient communication. The healthcare-based

interpersonal interaction and relationship between healthcare

providers (ie doctors, midwives, nurses, healthcare assistants and

record keepers) and the patients of Ogume primary healthcare

center. Interpersonal communication: Healthcare-related one-onone

verbal and non-verbal communication between the healthcare

providers and patients at the Ogume Primary Healthcare Center.

Health Seeking behaviour: Patients search for a perceived better

diagnostic and therapeutic treatment of diseases and sicknesses.

Theoretical Framework

The theory used for this study is the theory of Reasoned Action.

The theory was developed by Martin Fishbein and Icek Ajzen in

1967 and was derived from previous research that began as the

theory of attitude. The theory aims to explain the relationship

between attitudes and behaviours within human action. It is

used to predict how individuals will behave based on their preexisting

attitudes and behavioural intentions. In other words, an

individual`s decision to engage in a particular behaviour is based

on the outcomes the individual expects will come as a result of

performing the behaviour (Rogers-Gillmore et al., 2002). The ideas

within the theory have to do with an individual`s basic motivation

to perform an action. According to the theory, intention to perform

a certain behaviour precedes the actual behaviour Ajzen & Madden

[13]. Specifically, Reasoned Action predicts that behaviour intent

is caused by two factors namely, attitudes and subjective norms.

That is, behavioural intention is a function of both attitudes and

subjective norms toward that intention. Also, it is observed that,

depending on the individual and the situation, these factors might

have different impacts on behavioural intention (Miller, 2005). It is

further explained that the factor of attitudes and subjective norms

have two components each that influence behaviour intent. The

two components of attitudes are evaluation and strength of beliefs;

while subjective norms are made up of the components of normative

beliefs and motivation to comply Fishbein & Ajzen [14]. Invariably,

Reasoned Action theory is concerned about how the introspective

consideration of societal norms and personal values impact on

the individual`s decision-making process and eventual behaviour.

This theory is evidently relevant to this work because it is a study

of how cultural health beliefs in our societies and the individuals

understanding of same influence the decision of patients to behave

in conformity with medical instructions, otherwise known as

medical adherence behaviour.

Literature Review

Understanding Culture and Its Influence on Health Beliefs

According to Leininger [15], culture refers to the learned,

shared and transmitted knowledge of values, beliefs and

lifeways of a particular group that are generally transmitted

intergenerationally and influence thinking, decisions and actions

in patterned or in certain ways. In addition to this basic definition

offered by Leininger, Purnel and Paulanka [16] add that culture

is largely unconscious, both implicit and explicit, and dynamic,

changing with global phenomena. Recent consensus in public

health and health communication reflects increasing recognition

of the important role of culture as a factor associated with health

and health behaviours, as well as a potential means of enhancing

the effectiveness of health communication programmes and

interventions Institute of Medicine [17]. It is generally believed

that by understanding the cultural characteristics of a given group,

public health and health communication programmes and services

can be customized to better meet the needs of its members. That

is, the culturally bound beliefs, values and preferences a person

holds influence how he interprets healthcare messages Singleton

et al. [9]. In the view of Resniecow et al. in Kreuter and McClure [8],

concordance between the cultural characteristics of a given group

and the public health approaches used to reach its members may

enhance receptivity, acceptance and salience of health information

and programmes. In an attempt to capture this variability in the

cultural outlook of different peoples, Andrews & Boyle, in

Singleton,

Elizbeth & Krause [9] present health belief models that different

cultural groups use to explain health and illness into magicoreligious,

biomedical and deterministic beliefs. They explain that

magico-religious refers to belief in supernatural forces which

inflict illness on humans, sometimes as punishment for sins, in the

form of evil spirits or disease-bearing foreign objects as may be

found among Latin America, African American and middle Eastern

cultures; biomedical refers to the belief system generally held in the

US in which life is controlled by series of physical and biochemical

processes that can be studied and manipulated by humans, hence

disease is seen as the result of the breakdown of physical parts from

stress, trauma, pathogens or structural changes; and determinism,

the belief that outcomes are eternally preordained and cannot be

changed. Other sub-context cultures that have been advanced by

scholars to explain the relationship between culture and health

beliefs are familism and individualism Andrews & Boyle, in

Singleton et al. [9]; high context and low context cultures Gigar &

Davidhizar [18]; time orientation, present orientation and future

orientation cultures Purnel & Paulanka [16] etc. Each of these

cultural models are believed to influence health beliefs. Indeed,

all cultures have systems to explain what causes illness, how it

can be cured or treated and who should be involved in the process

Mc Lauglin & Braun [19]. The extent to which patients perceive

health information as having cultural relevance for them can have

a profound effect on their reception to information provided and

their willingness to use it. The fact that, cross-cultural variations

also exist within particular culture groups makes the culture-health

care relationship much more interesting.

Cultural Barriers that Affect Healthcare Provider/ Patient

Communication

Beliefs and values affect the doctor-patient relationship and

interactions Tongue et al. [7]. Divergent beliefs can affect healthcare

through competing therapies, fear of the healthcare system, or

distrust of prescribed therapies Diette and Rand [6]. The doctorpatient

relationship is one of the most unique and privileged

relations a person can have with another human being, just as having

access to a well developed and effective association is important

for the experience and objective quality of healthcare. Yet, over the

past few decades, a number of cultural barriers have converged to

reduce the ability of patients to have this archetypal relationship

with physicians Hughes, in Fowler [20]. Fowler categorizes these

cultural barriers into racial concordance of the doctor and patient,

language barriers and medical beliefs. The author cautiously

observes that another barrier to patient-physician communication,

even if they speak the same language, is low health literacy of

the patient which impairs ability to understand instructions on

prescription drug bottles, appointment slips, medical education

brochures, doctor’s directions and consent forms, and the ability to

negotiate complex healthcare systems Of all these cultural barriers,

the barrier of differences in medical beliefs are considered very

fundamental to creating disharmony in the health care provider

and patient communication relationship. As McLaughlin [19] points

out, each ethnic group brings its own perspectives and values into

the healthcare system, and many healthcare beliefs and practices

differ from those of the traditional American healthcare culture.

The expectation that the patients will conform to mainstream

values frequently creates communication and care barriers that

are further compounded by differences in language and education

between patients and providers from different backgrounds. Fowler

[20] maintains that when the two parties, comprising the doctor

and the patient, have different views on medicine, the balance of

cooperation and understanding can be difficult to achieve. This

perception gap may negatively affect treatment decisions, and

therefore may influence patient outcomes despite appropriate

therapy Platt & Keating [21]. Patients construct their own versions

of adherence according to their personal worldviews and social

contexts which result in a divergent expectation of adherence

practice Tongue et al. [7]; Sawyert & Aroni [22]; Middleton et al.

[23]. Therefore, it is important to identify and address perceived

barriers and benefits of treatment to increase patient adherence

to medical plans by ensuring that the benefits and importance

of treatment are understood Platt & Keating [21]. According to

reports, Bolivia’s healthcare system is particularly invaded by this

cultural barrier. As Bruun & Elverdam [24] put it, medical pluralism

is a common feature in the Bolivian healthcare system, consisting

of three overlapping sectors: the folk sector, the traditional sector

and the professional sector. Whether in Bolivia, India, China or

Africa, differences in medical health beliefs constitute a significant

barrier to effective patient and provider communication which is

absolutely necessary to giving and receiving adequate healthcare

Fernadez [25].

Health Disparities: The Importance of Culture and

Health Communication

Health disparities have been well documented even in systems

that provide unencumbered access to healthcare, suggesting that

factors other than access to care – such as culture and health

communication – are responsible Thomas, Fine & Ibrahim [26].

Some of the causal factors that have been blamed for the problem

of health disparities relate to individual behaviours, provider

knowledge and attitudes, organization of the healthcare system,

societal and cultural values. Accordingly, efforts to eliminate health

disparities must be informed by the influence of culture on the

attitudes, beliefs, and practices of not only minority populations

but also public health policy makers and the health professionals

responsible for the delivery of medical services and public health

interventions designed to close the gap Thomas et al. [26] Cultural

competence and patient centerednesss are two of such health

intervention programmes designed to improve healthcare quality

and thereby bridge the health disparity gap Saha et al. [27]. To

achieve this purpose, healthcare providers must see the patients

as unique; maintain unconditional positive regard for them; build

effective rapport; use the psychosocial model to explore patients

beliefs, values and meaning of illness, and to find common ground

regarding treatment plans. Evidently, cultural congruence of

patient, provider and message creates the right harmony for the

enhancement of interpersonal communication and care. Therefore,

Thomas et al. [26] propose the strategic matching of the cultural

characteristics of all populations ethnic, racial or minority group

with public health interventions designed to affect individuals

within the group. It is their conviction that this may enhance

receptivity to, acceptance of, and salience of health information

and programmes. This approach is consistent with the documented

evidence that factors such as belief systems, religious and cultural

values, life experiences, and group identify act as powerful filters

through which information is received, hence such factors should be

considered in the development of health communication campaigns

as well as in the healthcare provider and patient communication.

Cultural Explanation for Patients’ Non-Compliance with

Medical Recommendations and Prescriptions

A patients culture not only shapes the meaning of the

individuals behavior but also that persons health seeking and

health related behaviours. Medication adherence is a major

health behavior known to have a positive influence on patients

quality of life. Boykins & Carter [28]. An increasing number of

investigations have found positive relationships between clinicalpatient

communication, treatment compliance, and a variety of

health outcomes, including a better emotional wellbeing, lower

stress and burn out symptoms, lower blood pressure, and a better

quality of life (for both doctors and patients) Romani & Ashkar

[29]; Street et al. [30]; in Amutio Kareaga et al. [31]. For example, in

a study conducted by Fuertes et al. [32] using a sample of 101 adult

outpatients from a rheumatology clinic, the results demonstrated

that physician-patient working alliance predicted outcome

expectations, patient satisfaction and adherence. Conversely,

studies have also shown that non-adherence constitutes a major

problem in achieving desired outcomes in the management of

chronic diseases hypertension management Agyemang C et al.

[33] and other consequential implications for healthcare such as

deterioration of patient health conditions, worsening of disease,

treatment failures, increased hospitalization, death and increased

health care costs Osterberg & Blasche [12]. Incidentally, spirituality

and religiosity are some of the socio-cultural variables that have

been identified as determinants of such health behaviour as nonadherence

to medication and medical instructions. Accordingly,

there has been a growing tendency in the medical field to accord

recognition to these socio-cultural health beliefs in conformity

with the dictates of cultural competency and the perceived health

benefits Penman, Oliver & Harrington [34]. McLaughlin & Braun

[19] posit that cultural issues (such as spirituality and religiosity)

play a major role in patient adherence. This position is corroborated

by Miller, Thorsen & Mohr [35]; Ejikeme [36] in their submission

that spiritual and religious activities have been noted to strengthen

the faith of people and assist them with decision-making in health–

related practices. Therefore, scholars and healthcare practitioners

are better advised to channel more efforts towards maximizing

the utility benefits of spirituality and religiosity in eliciting patient

adherence behaviour.

Primary Healthcare Centres: Institution and Evolution

in Nigeria

The international conference on primary health defines

primary healthcare as “essential healthcare based on practical,

scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and

technology made universally accessible to individuals and their

families in the community through their full participation and at

cost that community and country can afford to maintain at every

stage of their development in the spirit of self determination”

WHO, in Metiboba [37]. The needs in the health sector led to the

establishment, among others, of primary healthcare centres (PCH)

as the centre piece of health development in Nigeria Akande [38].

The scheme which was established by the Gowon administration

in 1975 as part of the Third National Development Plan (1975-

1980) had the following objectives: increase the proportion of

the population receiving healthcare from 25-60 percent; correct

imbalances in the location and distribution of health institutions

and provide the infrastructures for all preventive health

programmes such as control of communicable disease, family

health, environmental health nutrition and others and establish a

health care system best adapted to the local conditions and to the

level of health technology Sorungbe, in Metiboba [37]. Accordingly,

the basic plan for the implementation of the scheme was to build

in each local government area a comprehensive health institution

that woud serve as the headquarters of the services, four primary

health centres and 20 health clinics designed for a population of

150,000 Akande [38]. Government had since improved on this

projection in terms of number of health centres available in each

local government in Nigeria. However, despite government’s good

intention in establishing this scheme, critical observers have

continued to complain about its poor implementation. Aside from

political, administrative and infrastructural factors militating

against the successful implementation of the scheme so far,

observers believe that the scheme still suffers from inadequate

awareness and mass mobilization for increased involvement of the

citizenry in PHC activities. For instance, Metiboba [39] insists that

a great proportion of the rural population in many communities do

not seen to know what PHC is all about, nor are they aware of the

various services under the scheme.

Ogume Primary Health Care Centre

There are a total of 15 primary health care centres in Ndokwa

West Local Government Area of Delta State and the Ogume Primary

Health Care Centre is one of them. Prior to the coming of the Ogume

primary health care centre in 2005, the building housing the centre

was first used as the Community’s local dispensary in 1955, before it

metamorphosed into a maternity clinic some years afterwards

Emenimadu [40]; Ochonogor [41]. Ever since, the maternity has

remained a prominent feature in the Ogume medical history. This is

so much so that, more than 10 years after it has been upgraded to a

primary health care centre, the indigenes still see it as a maternity

clinic. This lack of awareness is, according to accounts, one of the

reasons for the evident low patronage of the primary health care

centre by the male population of the community till date. Recently,

however, the state government constructed buildings meant for

two new primary health care centres at Ogbe Ogume and Ogbagu

Ogume quarters. These are yet to be occupied, except for the

overgrown weeds that now occupy the premises. In the meantime,

the male population continues to shun the health care centre that is

in use for some other speculative reasons.

Method of Study

The research design of this study was based on the triangulation

method. Wimmer and Dominick [42] define triangulation within

the context of mass media research as the use of both qualitative

and quantitative methods to fully understand the nature of a

research problem. The complementary use of both qualitative

and quantitative methods derives from a need to achieve a more

dependable and reliable result. Under quantitative, the survey

research method was adopted, while indepth interview was

adopted under the qualitative approach. A total of 120 respondents

were used for the survey method while another 14 respondents

were used for the indepth interview. All the respondents were

representative of patients in Ogume community receiving diagnostic

and therapeutic attention at the Ogume primary healthcare center.

Questionnaire and interview guide containing questions relevant

to the cultural health beliefs of the respondents and its influence on

their adherence to medical prescriptions were administered for the

survey and indepth interview methods respectively.

Area of Study

The area of study is the ogume community in Ndokwa West

Local government Area of Delta State. Ogume community is one

of the 16 clans that make up Ndokwa West Local Government

Area. Ogume is comprised of seven quarters namely, Ogbe-Ogume,

Ogbole, Umuchime, Igbe, Utue and Obodougwa. Although, these

seven quarters were originally given three primary healthcare

centers, situated one each in Ogbe Ogume, Ogbole and Utue quarters

only the one in Ogbe-Ogume is presently functional.

Population of Study

The population of study is represented here by the rural

dwellers in the seven quarters that comprise Ogume community.

The National Population Census Figure of 2006 credits Ogume

with a total of 28,654 persons. Given the benefit of population

growth and the time lapse between 2006 and 2017, there is need

to statistically project a population figure for Ogume in 2017 using

formula: PP = GP X PI X T; meaning

PP = projected population

GP = given population

PI = Population increase Index given as 2.28% by the United

Nations for developing nations all over the world

T = The duration of time between the year of given population

and year of study.

Therefore,

PP = 28,654 x 2.28% x 2017-2006

PP = 26, 654 x 2.28 X 11

PP = 28,654 X 0.0228X11

PP = 7,186.4

Actual population = 28654+7,186

35,840

Therefore the projected population of Ogume Community

which will be used for this study is 35, 35,840.

Sample Size and Sampling Technique

The study adopted the purposive sampling technique also

known as judgmental sampling. The merit of purposive sampling

stems from the fact that the researchers skill and fore-knowledge of

sample characteristics, to a large extent, guide researchers choice

of samples Nwodu [43]. The method imbues in the researcher the

prerogative of judgment in selecting his respondents based on

certain predetermined criteria. In this case, the predetermined

criteria for choosing the respondents are as follows: one, they

must be patients that have been in consultation with a healthcare

provider in the health care center; two, such patient would have

been in treatment at the health center between March and May,

2017; and three, they must be knowledgeable about the cultural

health belief practices in Ogume Community. That constitute the

focus of this study. After a series of visits to the health care center,

especially on Tuesdays and Thursdays which are their busiest days,

120 respondents were purposively chosen for the survey approach,

while another 14 respondents, two each from the seven quarters

of Ogume Community were purposively chosen for the indepth

interview.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Data obtained in this study are presented and analysed under

two separate categories. While data obtained through the survey

method are presented and analyzed using frequency table and

simple percentages for ease of understanding; data obtained

from the interview method are analyzed using the explanation

building technique. Under the survey approach, a total of 136

copies of questionnaires were distributed. Out of this number, 120

copies were returned and found valid for use, representing 82.2% return rate, while the unused 16 copies represent 11.8%. On the

other hand, 14 respondents were used for the in depth interview

approach and their responses were analyzed using the explanation

building technique.

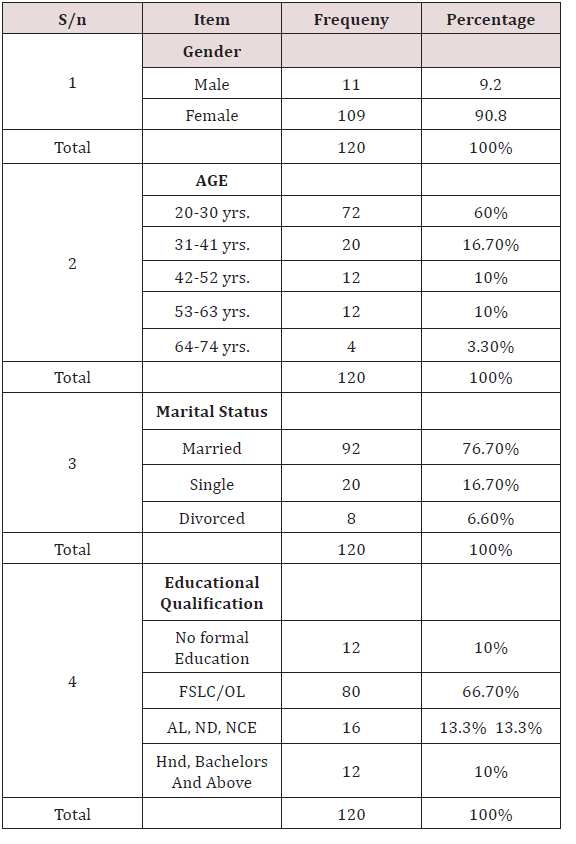

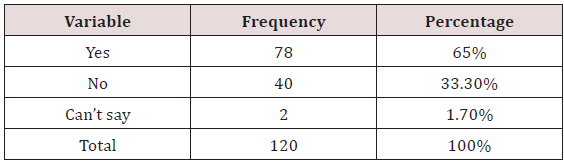

Table 1 above shows a sex distribution of female respondents,

109 (90.8%) as against 11 (9.2%) male respondents. It also

shows that majority of the respondents, numbering 72 (60%), are

between the age range of 20-30 years old. Others are 20 (16.7%)

respondents between ages 31 – 41; 12 (10%) respondents between

42 – 52, 12 (10%) respondents between 53-63 years and only 4

(3.3%) respondents in the age range of 64 – 74 years old. Also, there

is clear indication that majority of the respondents, 80(66.7%) are

barely educated with most of them possessing First School Leaving

Certificate (Primary Six) and ordinary level school certificate.

Others are 16 (13.3%) respondents with A/L, OND and NCE; 12

(10%) respondents with Bachelors and above. Another 12 (10%)

respondents did not have any formal education. On marriage, it

is evident from the records that majority of the respondents, 92,

representing 76.7% are married while 20 (16.7%) are single and 8

(6.6%) are divorced.

Table 1: Demographic Composition of Respondents.

Data from Survey Method

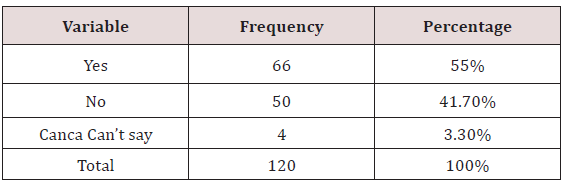

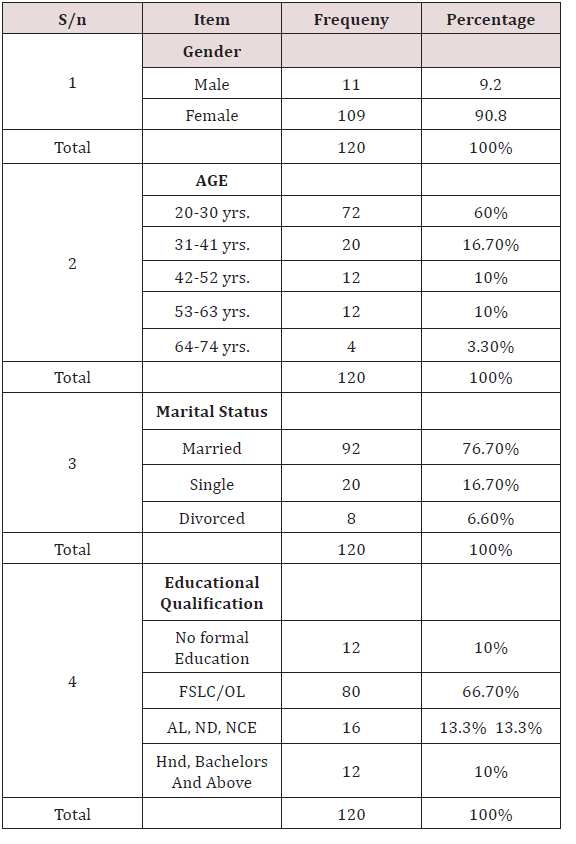

a. RQ. I: Do the cultural health beliefs of patients at the

Ogume health care centre influence their communication with

their health care providers? (Table 2).

Table 2: Respondents Views on How Cultural Health Beliefs

Influence Communication with Their Health Care Providers.

As is evident from data on the above table, 66 of the respondents

representing 55% expressed the opinion that their cultural health

beliefs impeded effective communication between them and their

health care providers; 50 of them, representing 41.7%, indicated

that their cultural health beliefs did not in anyway influence their

communication with their health care providers; while 4(3.3%)

respondents were not sure whether their cultural health beliefs

influenced their communication or not.

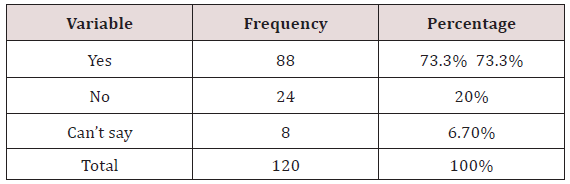

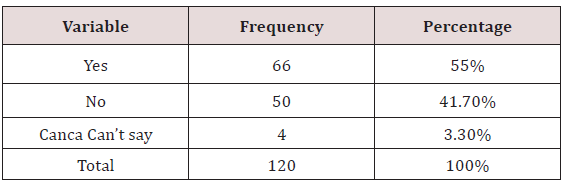

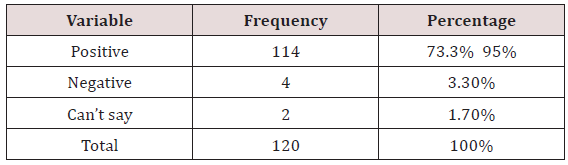

b. RQ. 2: Do the cultural health beliefs of patients at Ogume

Health Care Centre influence their adherence to the health care

providers prescriptions? (Table 3).

Table 3: Respondents Position on the Influence of Their Cultural

Health Beliefs on their Adherence to the Health Care Providers

Prescriptions.

From the above table, it is evident that the adherence behaviour

of a high majority of the respondents was influenced by their cultural

health beliefs. There are a total of 88 (73.3%) of such respondents.

On the other hand are those respondents, 24(20%) who believe

that their adherence to medical advice The management of the

health centre blames this low patronage of men on cultural beliefs

which make it a taboo for most men in the community to see a 1-7

day old baby. They explain that in order to avoid such occurrence,

which is very likely in the health centres’ primary midwifery

service, the men keep their distance from the health centre. Other

opinions blame it on lack of awareness among the male population

that the health centre offers healthcare services outside of the more

common antenatal, midwifery and child immunization functions.

was not affected by their cultural health beliefs. Another group

of respondents, numbering 8(6.7%) failed to venture an opinion,

either way.

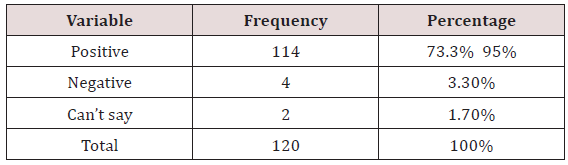

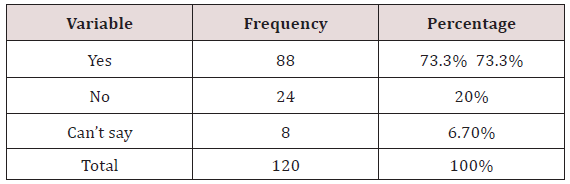

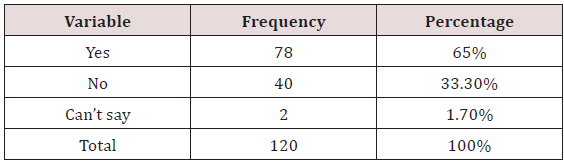

c. RQ. 3: Do the cultural health beliefs of patients at the

Ogume health care centre influence their health seeking

behaviour? (Table 4).

Table 4: Respondents Perception of How Their Cultural Health

Beliefs Influence Their Health Seeking Behaviour.

The above given responses show that virtually all the

respondents, 114 amounting to 95%, believe that their cultural

health beliefs influenced their health seeking behaviour. On the

other hand, a few of them, 4(3.3%), are of the opinion that their

health seeking behaviour is not influenced by their cultural health

beliefs. In between these positions are 2(1.7%) respondent who

chose to sit on the fence on the question as to whether or not their

cultural health beliefs influence their health seeking behaviour

or not. The above table shows that 78(65%) of the respondents

consented to the fact that the family members influenced them on

the choice of traditional medicine for treatment, while 40(33.3%)

answered in the negative. Only 2(1.7%) respondents could neither

say yes nor not (Table 5).

Table 5: Respondents Perception on Family Members Influence

in Taking Traditional Medicine.

Data From Indepth Interview

The researcher subjected 14 of the purposively selected

respondents, two each from the seven quarters that comprise the

Ogume Community, to in-depth interview. Four basic questions

along the lines of the study research questions guided the interview

sessions. The responses are analysed as follows:

Influence of Cultural Health Beliefs on the Communication

between the Health Care Providers and Patients

On this count, majority of the interviewees expressed the

opinion that their cultural health beliefs greatly impeded their

communication with their health care providers. They explained

that their mind-set, arising from prior cultural health beliefs in

traditional medicine, affected their trust and confidence in the

competence of orthodox health care providers in the treatment of

certain ailments. In the words of one of such respondents, Chief

Lucky Ogwu, “there is a limit to what oyibo doctors can treat”.

He listed some of these as bone fractures, diabolic poisoning and

convulsion in children. According to him, in situations where

orthodox medicine resorts to amputation for orthopaedic care,

traditional medicine successfully sets the fractured area straight

with the use of herbal applications. Another of the respondents

who shares this opinion, Mrs. Cecilia Opone, was emphatic that no

matter what the health care providers say, she will continue to take

herbal medicine for her antenatal care. According to her, herbal

medicine helps reduce the size of the placenta, which she calls “our

mother” and thereby, potentially reducing the risk of complicated

labour. However, on the reverse side, a few of the respondents said

their cultural health beliefs do not influence their communication

with health care providers. One of such respondents, Mrs. Abigail

Oji, said that she had relied on traditional medicine during her first

pregnancy and lost the baby in infancy. Ever since, she has resorted

to orthodox medicine with better results. Hence, she now follows

medical instructions to the letter.

Influence of Cultural Health Beliefs on Patients’ Adherence

to Health Care Providers Prescriptions

Majority of the respondents admitted that their cultural health

beliefs negatively influenced their willingness to adhere to health

care providers prescriptions. In her reaction, Mrs. Paulina Nzeukwu

complained that after several visits to the health center, she

resorted to herbal medicine to solve the problem of the mysterious

pain in her stomach which several X-rays could not detect. Hence,

she discontinued her orthodox medication. In his account, Chief

Lucky Ogwu insisted that you cannot mix them (English and

Native medicine) because even English medicine are made from

herbs too. According to him, “mixing them could cause overdose”.

Hence, anytime he takes traditional medicine, he stops his orthodox

medication regardless of health care providers instructions. On the

flipside, a few of the interviewees maintained that they strictly

adhere to health care providers instructions.

Influence of Cultural Beliefs on Patients Health Seeking

Behaviour

All the respondents were emphatic that their health seeking

behaviour towards a perceived better and more satisfactory

treatment was positively influenced by their cultural beliefs in

the diagnostic and therapeutic efficacy of medicine, orthodox or

traditional. As one of the respondents who opted for anonymity, put

it, “if I do not seek for better treatment where I believe I can get it,

that means I am playing with my life”. This sentiment summarized

the feeling of all the interviewees on this issue.

Discussion of Findings

a. Objective I: set out to establish whether cultural

health beliefs influence health care providers and patients

communication at the health care centre. The findings show

that patients’ cultural health beliefs adversely influenced

their communication with the health care providers. This

communication problem stemmed from the contrariness in the health beliefs of both parties. This finding echoes earlier

findings by researchers in this area. Fernandez [25] had found

that differences in medical health beliefs constitute a significant

barrier to effective patient and provider communication which

is absolutely necessary to giving and receiving adequate

healthcare. Fowler [20] in his own study found that when the

two parties, comprising the patient and the provider, have

different views on medicine, the balance of cooperation and

understanding can be difficult to achieve. This is also consistent

with the findings of McLaughlin and Braun [19] that the

barriers of differences in medical beliefs are fundamental to

creating disharmony in the health care provider and patient

communication.

b. Objective 2: The finding that patients’ health beliefs

negatively influenced their adherence to health care providers

prescriptions conforms with the findings of earlier works on

the subject. McLaughlin and Braun [19] had found that cultural

issues such as religiosity and spirituality play a major role in

patient adherence. Schouten [44] found that there is more

misunderstanding, less compliance and less satisfaction in

medical visits of patients with differing health beliefs from

those of their health care providers. This finding resonates with

those of Thorsen & Miller [35]; Ejikeme [36] who found that

spiritual and religious activities have been noted to strengthen

the faith of people and assist them with decision making in

health related practices such as adherence. Other studies also

found that patients construct their own personal worldviews

and social contexts which results in divergent expectations

of adherence practice Tongue et al. [7]; Sawyer & Aroni [22];

Middleton et al. [23].

c. On objective 3: which is how patients’ cultural health

beliefs influence their health seeking behaviour, the findings

show that majority of the respondents’ health seeking

behaviours were influenced by their cultural health beliefs.

The results evidenced that the patients’ health beliefs in the

diagnostic and therapeutic power of medicine propelled

them to seek for help from orthodox or traditional doctors,

depending on the cultural perspectives of individual patients.

While the majority sought help in traditional medicine, others

who believed otherwise sought better and more satisfactory

medical attention from orthodox healthcare providers. The

findings here correspond with those of Ojua [10]; Katung [11];

Ejikeme [36] that the typical Nigerian rural dwellers resort to

traditional medicine on the one hand; and to chemist shops,

health centres and hospitals on the other hand for the treatment

of sicknesses and diseases. In a related study on the Bolivian

health care system, Bruun & Elverdam [24] had found a similar

feature of medical pluralism in health seeking behaviour. Table

1 revealed a low level of patronage of the health centre by the

male population of the community. The management of the

health centre blames this low patronage of men on cultural

beliefs which make it a taboo for most men in the community to

see a 1-7 day old baby. They explain that in order to avoid such

occurrence, which is very likely in the health centres’ primary

midwifery service, the men keep their distance from the health

centre. Other opinions blame it on lack of awareness among

the male population that the health centre offers healthcare

services outside of the more common antenatal, midwifery and

child immunization functions. This finding is in tandem with

the finding of Resniecow et al in Kreuter & Mc Clure [8] that,

concordance between cultural characteristics of a given group

and the public health approaches used to reach its members

may enhance receptivity, acceptance and salience of health

information and programmes. Also, the findings lend credence

to an earlier finding by Metiboba [39] that a great proportion

of the rural population in many communities do not seem to

know what primary health care centre is all about, nor are they

aware of the various services under the scheme. Furthermore,

Table 5 shows clearly that an overwhelming number of the

respondents were influenced by family members to take

traditional medicine. This finding corroborates an earlier

finding by Andrews & Boyle (2008) that cultural systems such

as familism and individualism affect the health beliefs and

health behaviours of patients in African Communities. Again,

the findings of this study are consistent with the principles

that govern the theory of reasoned action. Specifically,

reasoned action predicts that behavioural intents are caused

by individual attitude and the subjective norms towards that

intention. It is further stated that, depending on the individual

and the situation, these factors might have different impacts on

behavioural intention Miller [45]. This theory is relevant to this

work because it is a study of how the patients’ cultural health

beliefs and understanding of same influence their decision to

were influenced by cultural health beliefs and advice of family

members. Finally, it is instructive to note that the findings of the

two methods used for this study (survey method and indepth

interview) are constituent with each other with the findings

of one reinforcing and lending credence to the findings of the

other.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The pre-eminence of good health over all other concerns

of man is an incontrovertible fact of life. It is for this reason that

responsible and responsive governments all over the world

establish hospitals, train medical personnel and embark on all

other extensive medical programmes designed to secure an

effective health care system for its citizens. As part of this extended

programme, health communication activities are carried out to

inculcate health literacy in patients that will enable them make

informed personal health choices. Edgar & Hyde [3] recommend

interpersonal communication between health care providers

and patients as one of the most effective strategies for achieving

positive health outcomes in patients. Unfortunately, studies have shown

that the goal of achieving effective communication between

healthcare providers and their patients has always been beset

by a number of barriers one of which is patients’ cultural beliefs

Diette & Rand [6]; Tongue et al [7]; Ejikeme [36]. Incidentally,

the findings of this study corroborate these earlier findings as it

relates to cultural health beliefs constituting noise in the channel

of communication between health care providers and patients, and

thereby, impeding effective communication between the parties

[46,47]. These cultural health beliefs, usually expressed in medical

plurality and non-adherence to orthodox medical prescriptions;

come with dire consequences among which are deterioration of

patient health condition, worsening of disease, treatment failures,

increased hospitalization, deaths and increased healthcare costs

Osterberg and Blasche [12]. Given the consequences of cultural

health beliefs to effective provider patient communication and its

implications for patient health outcomes, the paper recommends

as follows:-

a. One, that there should be enhanced facilitation of health

communication and education for health care providers and

receivers alike at the rural level on the significance of cultural

health beliefs in achieving a sustainable health care system.

b. Two, that the Ministries of information and health at the

local government areas should embark on concerted public

awareness campaigns directed at the rural populace on the

availability and benefits of the primary health care centres

closest to them.

c. Three, that professional communicators who are

indigenes of the rural communities should be drafted as part

of the medical staff at primary health care centres with the

aim of fostering a trust-yielding and confidence-boosting

interpersonal relationship between the health care providers

and patients at the centres.

d. Four, that town hall or village square meetings should

be regularly organized, with qualified medical personnel as

speakers, to address the rural dwellers on the risk implications

of non-adherence, self-medication and such other abuses as

well as disabuse their minds about certain traditional medicine

related misconceptions they have.

e. Finally, that there should be more localized studies

on the all-important place of cultural health beliefs and

their implications, not only for effective provider patient

communication but also for eventual positive patient outcomes.

For more Lupine Publishers Open

Access Journals Please visit our website:

http://lupinepublishers.us/

For more Research

and Reviews on Healthcare articles Please Click Here:

https://lupinepublishers.com/research-and-reviews-journal/

To Know More About Open Access

Publishers Please Click on Lupine

Publishers

Follow on Linkedin : https://www.linkedin.com/company/lupinepublishers

Follow on Twitter : https://twitter.com/lupine_online